It’s Day 5 of For the Love of Film (Noir) — don’t forget to or use the button on the right. And if you are interested in boatloads of great links to musings on film noir and its films, scroll down this page at Self-Styled Siren or over at Ferdy on Films. This is wonderful material! (Also see today’s Blogathon Notes.)

One of the few things I’m certain about with the movies that started this whole film noir business, movies from the forties and fifties like The Big Heat, Double Indemnity, or Gilda, is that they were not aware of themselves as being in a genre called film noir. They might have thought of themselves as B-movies, crime movies or pulp, but not film noir. Categorization like that always comes after the fact.

But once an approach or style is identified, like film noir, subsequent movies taking that approach are self-aware. They see themselves as film noir and inevitably try to replicate the approach. They may try to do much more, but they can’t be made the same way as the original film noirs were. Awareness affects what is being created.

Just as you can’t see the same movie twice (not in the same way), you can’t make the same kind of movie twice. But you can come damn close!

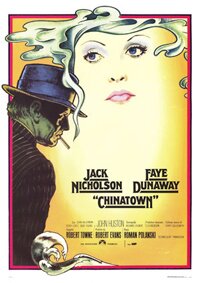

Chinatown (1974)

Directed by Roman Polanski

Chinatown, a wonderful movie, is an example of what a script can do for a film.

It’s like finding the right music at a party. Someone feels compelled to dance, then another and another. Soon, everyone’s up dancing. And dancing well.

In Chinatown, just about every artist is dancing their damnedest because the script has pulled them onto the floor. Director, actors, lighting people, costume designers … they’re all performing at their highest level.

It’s Robert Towne’s script that has done this.

One of Roman Polanski’s great talents is creating mood and few films do it so well and so quickly as the opening of Chinatown. I can’t think of many movies I would watch simply to see the opening credits but the look and the marvellous music of the introductory credit sequence is just so good with its period lettering and sepia tone (which carries through the movie), that you’re hooked even before the movie has presented its opening shot.

Modelling itself on the film noir style (particularly films like Howard Hawks’ movie The Big Sleep), the film’s mystery is created by presenting the story through the eyes of detective Jake Gittes, the Jack Nicholson character. We know what he knows, we’re puzzled by what he’s puzzled by, we’re misled by what misleads him. In fact, just as Bogart was in just about every scene of The Big Sleep, Nicholson is in just about every scene in Chinatown, either as a participant or as an observer.

But the film isn’t dependent on Nicholson. Faye Dunaway is perfectly cast as the enigmatic, and troubled, Evelyn Mulwray. It’s hard to imagine anyone else but Dunaway in that role. The movie is also bolstered by brilliant supporting performances, particularly John Huston as Noah Cross.

I also love the leisurely way the movie unfolds. Unlike the quick cuts and thrumming soundtrack of most current movies, Polanski takes his time. And it works so well. This may be the reason why it works. You’re seduced by the mood, and become involved with the characters, and thus the story.

Chinatown is a great, fascinating movie that illustrates the importance of beginning with a great script.

With the DVD … it’s okay. Not great, could be a lot better, but adequate. It’s largely clean and clear, but certainly not on the pristine level.

This is partly due to it being an older film (1974). For extras, there is really just one (I don’t count trailers as extras).

There is a documentary of sorts. It features interview clips with director Roman Polanski, writer Robert Towne, and producer Robert Evans.

There are some interesting comments, but there is really no depth to it … Par for the course with DVD extras.

(Note: This was written more than 10 years ago. The DVD comments refer to an early DVD release. The movie has since been released in a “special edition” which, I believe, is an improvement.)

Key Largo (1948)

Key Largo (1948) Having left the Army, ex-Major Frank McCloud goes to Key Largo to pay respects to the family of one of the soldiers under his command who was killed in action. McCloud seems a bit aimless having left the army; this obligation he feels to visit the family is about the only purpose he has at this stage in his life.

Having left the Army, ex-Major Frank McCloud goes to Key Largo to pay respects to the family of one of the soldiers under his command who was killed in action. McCloud seems a bit aimless having left the army; this obligation he feels to visit the family is about the only purpose he has at this stage in his life. What the movie does is to bring all these characters together in one place and confine them in close quarters. You feel the walls closing in, so to speak, as the winds get stronger and shutters are closed. They are all closed in; sunlight vanishes.

What the movie does is to bring all these characters together in one place and confine them in close quarters. You feel the walls closing in, so to speak, as the winds get stronger and shutters are closed. They are all closed in; sunlight vanishes. Tension builds in the movie partly because of the storm, partly because Johnny Rocco gets increasingly anxious about completing his deal, but also because of the forward and backward pull between the characters: Johnny’s will to go back to the past; McCloud and the others’ desire to break free and go forward into the future.

Tension builds in the movie partly because of the storm, partly because Johnny Rocco gets increasingly anxious about completing his deal, but also because of the forward and backward pull between the characters: Johnny’s will to go back to the past; McCloud and the others’ desire to break free and go forward into the future. Murder, My Sweet (1944)

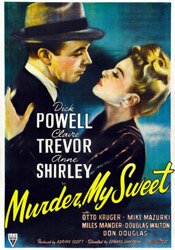

Murder, My Sweet (1944) For many people Humphrey Bogart (The Big Sleep) is the Philip Marlowe. But just today I came across a review where the writer was claiming the best Marlowe was Robert Mitchum in 1975’s Farewell, My Lovely.

For many people Humphrey Bogart (The Big Sleep) is the Philip Marlowe. But just today I came across a review where the writer was claiming the best Marlowe was Robert Mitchum in 1975’s Farewell, My Lovely. In other words, the movie twists quite a bit and in many cases the twists are arbitrary for the sake of being a twist and to sustain the mood. But they don’t make a lot of sense. Yet in a film noir, you can often get away with that because the movie is less about plot and more about atmosphere, characters, character relationships … and lighting and camera focus.

In other words, the movie twists quite a bit and in many cases the twists are arbitrary for the sake of being a twist and to sustain the mood. But they don’t make a lot of sense. Yet in a film noir, you can often get away with that because the movie is less about plot and more about atmosphere, characters, character relationships … and lighting and camera focus. Being film noir, we also get a femme fatale. Claire Trevor is Mrs. Helen Grayle, aka Velma. Director Edward Dmytryk introduces her to us legs first, underlining the character’s sexual nature and involvement with the story. But the there is also Anne Shirley as Ann Grayle, step-daughter and enemy of the second Mrs. Grayle (Velma). It’s easy to see why.

Being film noir, we also get a femme fatale. Claire Trevor is Mrs. Helen Grayle, aka Velma. Director Edward Dmytryk introduces her to us legs first, underlining the character’s sexual nature and involvement with the story. But the there is also Anne Shirley as Ann Grayle, step-daughter and enemy of the second Mrs. Grayle (Velma). It’s easy to see why. But the movie isn’t just about this. It begins with a man named Moose (Mike Mazurki), who is just out of jail and looking for his Velma.

But the movie isn’t just about this. It begins with a man named Moose (Mike Mazurki), who is just out of jail and looking for his Velma.