Lawrence of Arabia is the Icarus myth. A hero starts out at neither the bottom nor top but somewhere around the middle, perhaps a bit lower than that, then ascends. But he gets too close to the sun and falls. The movie looks at that, asks why and suggests the answer is the usual thing: hubris.

Can a film noir be too perfectly noir?

I think I’m one of the few people who doesn’t care much for Out of the Past. It may be that for me the closer a movie gets to film noir, the less it appeals to me. I can’t argue with any of the superlatives used to describe this one. But despite all it does right in terms of noir, I can’t get terribly enthused.

Cautionary tale: Kingdom of Heaven

Ridley Scott likes his movies big. In 2005, he made one of them — an old school sword-and-sandals epic called Kingdom of Heaven that despite its action scenes and moments of brutal violence, is overall a surprisingly quiet, thoughtful cautionary tale about the hazards of extremes.

A curious thriller: So Long at the Fair

Prior to moving out to California and Hollywood, Jean Simmons was primarily in British films. This makes sense given that she was British. So Long at the Fair is one of those movies. Depending on your age and interests, however, you may recall her best as Rear Admiral Norah Satie in Star Trek: The Next Generation (Episode: The Drumhead).

The great and debatable Red River

I really go on a ramble here about this movie, though it is more a ramble about John Wayne’s acting and speech pattern than the film. This is considered one of the great westerns by many and I would be among them. However, while I like Wayne in it and think it’s one of his best roles, it is not my favourite John Wayne performance.

The curious hybrid called Deep Impact

When is a disaster movie not a disaster movie (even though it’s a disaster movie)? The answer is when it’s a Mimi Leder directed disaster movie and the usual trappings of the genre are downplayed and others, usually dealt with in an offhand manner, are lingered over.

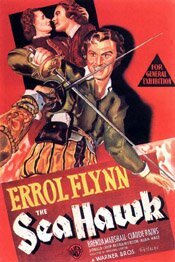

The impish Errol Flynn in a swashbuckler

A few years ago I bought a fistful of Errol Flynn movies that were in one of those many Warner Brothers collections. I had only vague memories of Flynn movies but was curious having seen The Adventures of Robin Hood and, a few years earlier, having read his autobiography, My Wicked, Wicked Ways (recommended, by the way — it is so much fun to read).

Among the movies in the collection was the one I scribbled about below, The Sea Hawk. Interestingly, just as Robin Hood was directed (in part) by Michael Curtiz, he also directs this movie. He seems to have been aware of what Flynn brought to these movies and was very good at getting it.

The Sea Hawk (1940)

The Sea Hawk (1940)

Directed by Michael Curtiz

I’m halfway through Errol Flynn: The Signature Collection and I think I’ve hit the real gem of the lot. (Not that the others aren’t good too.) It’s The Sea Hawk and it really does put the “swash” in swashbuckler.

It’s absolutely brilliant and in a number of respects. I can’t help comparing it to The Adventures of Robin Hood. It has much of the same feel while at the same time has a little something different.

For one thing, both films capture a sense of fun and exuberance. Both also manage to be rousing costume adventures without any sense of self-consciousness though The Sea Hawk differs slightly in that Errol Flynn plays the British pirate Captain Geoffrey Thorpe with a kind of very contained impishness.

His captain is apparently quite serious, patriotic and heroic, yet every now and then he seems to be restraining a smile or grin.

As someone in the special feature on the DVD says (The Sea Hawk: Flynn in Action), it’s almost as if Flynn is asking the audience, “Are you really buying this?”

But in these Flynn movies this kind of feeling is not one of mocking the audience but of having fun with them. Flynn seems to play his swashbuckling roles the way the early Springsteen played concerts – the more fun the audience had, the more fun he had and together they create a kind of synergistic relationship.

Another fascinating way in which The Adventures of Robin Hood and The Sea Hawk compare is in their look. Where Robin Hood is an incredibly exuberant display of colour, The Sea Hawk is nothing less than a magnificent example of black and white. (Although I could have done without the Panama scenes done in sepia.)

The sea battles between the ships are fabulous.

We know from recent films like Master and Commander that great sea battles can be done in colour but I’ll take The Sea Hawk’s scenes anytime. (It’s also incredible to think these were done on sets.)

There is also a great sword fight (as there must be to conclude an Errol Flynn swashbuckler) where, again, the black and white scenes with their use of light and shadow are exceptional. I loved the great shadows on the walls during the struggle.

The Sea Hawk is about as close to the quintessential swashbuckler as you can get. It has Errol Flynn, the man who pretty much defines the hero of such movies.

It has the great set pieces like the sea battles and the swordfights. And it has the music that has influenced the sound of almost all heroic adventures.

Credit for the music goes to Erich Wolfgang Korngold. His score (which is apparently not just rousing but quite clever as it uses, in part, themes from the earlier The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex but in a reworked form), is operatic which, if you think about it, is really what such romantic adventures require.

I really didn’t know a great deal about The Sea Hawk before watching it. And to be honest, I wasn’t expecting a great deal. I basically put it in the DVD player because I wanted to watch something and I hadn’t seen this one yet.

As often happens, when I was least expecting it, I encountered a wonderful movie. Highly recommended.

(The Sea Hawk also aired last night on TCM. I missed it but I may watch my copy again tonight. The above was written roughly about April 2005.)

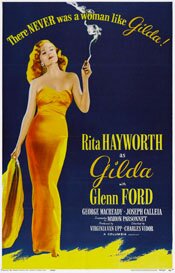

Abuse never looked as beautiful as it does in Gilda

It’s Day 7 of For the Love of Film (Noir) — don’t forget to or use the button on the right. We’re near the end, so now is the time to donate if you haven’t already. If you are interested in boatloads of great links to musings on film noir and its films, scroll down the page at Self-Styled Siren or over at Ferdy on Films. This is wonderful material!

As much attention as Gilda gets for the beauty and sexiness of Rita Hayworth, what always strikes me is what a mean-spirited, spiteful bastard Glenn Ford is as Johnny Farrell. For about ninety percent of the movie he is abusive and hateful.

Being on the receiving end of it all, Hayworth’s Gilda is a beautiful cry for help. Intentional or not, this movie is a portrait of abuse: verbal, psychological and physical.

Gilda (1946)

Gilda (1946)

Directed by Charles Vidor

The opening of Gilda may be the perfect image for film noir. The camera tilts up from ground level revealing Glenn Ford as Johnny Farrell. He is on his hands and knees, disheveled, hair hanging down over his eyes, as he determinedly rolls his dice.The camera angle makes those dice look huge.

It is almost as if Ford is on the ground groveling.

Compare that to all the heroic shots of John Wayne in those innumerable westerns. Noir and westerns are two sides of one coin, the hero. Being noir, however, the hero must have his femme fatale to muddle up the works for him.

Inevitably, we soon encounter Rita Hayworth as Gilda.

What we soon learn about Johnny and Gilda is that they are really just small time people scrambling to make it in a less than friendly world. Neither really has any admirable characteristics, at least not through most of the movie. (At one point Gilda says, “If I’d been a ranch, they would have called me the Bar Nothing.”)

Yet somehow, for some reason, we’re on their side. Maybe it’s because in the world they inhabit they are slightly better than the other characters and we side with them because we identify with the struggles and compromises made to live in the world.

I’m always fascinated by the dichotomy of westerns and noirs and the idea that they are one thing seen from opposing angles.

When we first meet Gilda she appears like a jack-in-the-box. Her head pops up in such a way that we can’t help but see the lush and luxurious hair and the smile that seems to suggest so much, like playful sex. Everything about Gilda is sex.

For her, it’s both weakness and strength.

We also know immediately, from Johnny’s reaction to Gilda, that “something’s going on there.” They know one another; there is a relationship between them, one that has clearly soured.

The movie is also about relationships that are off in some way. There is anger, even outright hate between Johnny and Gilda, especially on Johnny’s part. As much of a weasel he was in the film’s beginning (and still is, though he has cleaned up his act), he is equally unforgiving. Gilda, encountering his spite, responds in kind.

What we’re not quite sure of is the why of it all. (I don’t recall if this is ever explained other than the fact that Johnny left her, though reasons may be suggested.)

Perhaps what is really askew between Johnny and Gilda is that neither knows what they want. Johnny wants money and power, though I imagine he would be hard pressed to answer why (beyond getting out of the gutter). It seems to be a deflective desire, something pursued in order to forget.

Gilda, on the other hand, hasn’t a clue what she wants. She is entirely reactive – to Johnny’s hate, to the men that use her, to her lack of purpose. (However she, as opposed to Johnny, begins to have an idea as the movie progresses.)

We, on the other hand, pretty much know what both want but won’t admit to themselves: each other. They live in a world of denial; neither wants to articulate the truth about their feelings.

Then there is Ballin Mundson (George Macready). Some argue there is a homoerotic element to Gilda in the relationship between Mundson and Johnny.

Given when the film was made and the shadow of the Hays Code, it would have been difficult to make something like that obvious so, initially, the argument may seem a bit of a stretch.

But the more you think about the movie the more it makes sense. Much of what happens in the film’s first half seems unlikely and arbitrary unless you see a homosexual element to it. One of the things that first struck me was how absurdly convenient it was that Johnny, in a shady part of town, is rescued from thieves by a wealthy man who just happened to be in that end of town. It makes sense, however, if he is in that part of town looking to pick someone up for sex.

The relationship that develops between Johnny and Mundson makes more sense in this context.

Johnny’s taken into Mundson’s world, given a position of authority and trust, becomes his right hand man, given access to Mundson’s wealth (including the safe) … And it all happens very quickly.

It all seems a little too convenient unless you consider there is something like a gay relationship between the two (though not a healthy gay relationship). It gains credibility if you see the relationship of Johnny to Mundson as similar to Sunset Boulevard‘s Joe Gillis to Norma Desmond.

It also adds another element to Johnny’s dislike of Gilda: there is a previous relationship between them but there is also the fact that, with Gilda as Mundson’s new wife, she is intruding on Johnny’s position.

Though it may be a bit of a long shot as far as interpretations go, I like to think that homoerotic aspect is there. It helps make sense of what are otherwise puzzling story elements and also adds a nice bit of irony in that it is present in a movie known for its heterosexual quality, the “love goddess” Rita Hayworth, famous for making heterosexual men crazy with longing.

When you get past the glitz and spectacle of Rita Hayworth’s famous sultry sexuality in the movie, the more you can’t help thinking this is one crazy movie about abuse and aberrant psychology. And you know, despite the happy gloss of the ending, that it will continue. Johnny and Gilda may have mended their fences and be doe-eyed once again, but the abuse will be back.

(Note: Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford would be teamed again six years later in 1952’s Affair in Trinidad, an attempt to jump start Rita’s career and a poor knock off of Gilda.)

Film noir doesn’t always mean good: Dark Passage

It’s Day 6 of For the Love of Film (Noir) — don’t forget to or use the button on the right. And if you are interested in boatloads of great links to musings on film noir and its films, scroll down this page at Self-Styled Siren or over at Ferdy on Films. This is wonderful material!

As much as I like movies in the film noir category, particularly those from the forties and fifties, the term is not a synonym for good. As with any type of movie — screwball, romance, western, drama — it has its clunkers.

Of course, everything is subjective. As you’ll read below, I don’t have a high opinion of Dark Passage. Maybe the problem isn’t the movie but me. To be fair, there is this review over at Noir of the Week. As for mine …

Dark Passage (1947)

Dark Passage (1947)

Directed by Delmer Daves

Of the four movies Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall made together, Dark Passage is easily the weakest. (Their other movies together were To Have and Have Not, The Big Sleep, and Key Largo.) It’s a film noir that has what it thinks is a neat idea — the first third of the movie uses a “first-person” camera, meaning the central character is the camera viewpoint.

But it falls flat.

In fact, the gimmick pretty much ruins the film because we don’t get to see (and therefore connect with) Humphrey Bogart’s character. In the first third, we don’t see him period. He is the camera viewpoint. In the second third, his head is bandaged (due to plastic surgery to alter his identity).

We don’t actually see Bogie till a large chunk of the movie is over. By the time we do, we’re bored.

Bogart plays a character wrongly accused and convicted of murder. The movie opens with his escape. On the run, he is rescued by Lauren Bacall’s character. (Everyone Bogart runs into in the movie conveniently has some connection to the story.)

Bogart plays a character wrongly accused and convicted of murder. The movie opens with his escape. On the run, he is rescued by Lauren Bacall’s character. (Everyone Bogart runs into in the movie conveniently has some connection to the story.)

A helpful cab driver later recommends a shady plastic surgeon to Bogart’s character. Bogart gets his face changed then goes off in search of the criminals who framed him so he can prove his innocence.

Despite trying, the movie never gets very interesting. For one thing, there is very little to relieve the darkness of the noir approach. There is also little chemistry between Bogart and Bacall and this is largely because they play so few scenes together, at least in the first two thirds.

The characters do have scenes, but since Bogart isn’t physically in them (because of the camera viewpoint or because his head is wrapped in bandages and he can’t talk), the Bogie-Bacall magic is absent.

The other problem are the improbable conveniences mentioned above — the helpful cab driver, a guy who picks up Bogart when he is hitchhiking, Bacall’s appearance. It’s all a little too improbable.

The other problem are the improbable conveniences mentioned above — the helpful cab driver, a guy who picks up Bogart when he is hitchhiking, Bacall’s appearance. It’s all a little too improbable.

The only time we get a sense for an interesting story is at the very end when Bogart and Bacall have fled to South America. Suddenly the heavy handed noir atmosphere is relieved and we get something that has more of the atmosphere of Casablanca or To Have and Have Not.

It seems clear that the movie has misread what made Bogart and Bacall so interesting together. It certainly misreads Bogart.

Despite the success of movies like The Big Sleep and The Maltese Falcon, it wasn’t the noir genre that made Bogart popular. It was that he was playing a flawed romantic hero within them.

Despite the success of movies like The Big Sleep and The Maltese Falcon, it wasn’t the noir genre that made Bogart popular. It was that he was playing a flawed romantic hero within them.

In Dark Passage he simply plays a schmuck floundering around trying to prove his innocence. He doesn’t play a strong character. If anything, the character is rather weak.

And so we end up with a tedious movie, one that relies on a gimmick rather than the power Bogart and Bacall could bring to the screen.

They are wasted in this movie.

On Amazon:

- Dark Passage

- Bogie and Bacall – The Signature Collection (includes: The Big Sleep, Dark Passage, Key Largo and To Have and Have Not)