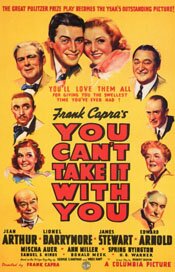

Last night TCM ran Frank Capra’s You Can’t Take It With You and while I had the same response as what follows below — this is a very chaotic and cacophonous movie — this time I adapted to it better and noticed just how good Edward Arnold is in it. Though an ensemble piece, this is really his movie.

Capra is the kind of director people either really love or really hate. I lean more to the former but I do understand the feelings of the latter. He can be a bit much with his moralizing and sentimentality. In this case, it wasn’t those elements I found off-putting. It was the bedlam.

You Can’t Take It With You (1938)

You Can’t Take It With You (1938)

Directed by Frank Capra

Sometimes you can have all the right elements but they somehow don’t quite gel. This is the case with Frank Capra’s 1938 You Can’t Take It With You.

It has all the Capra elements, has the Capra touch, and even has Capra stalwarts like Jimmy Stewart and Jean Arthur, Lionel Barrymore and Edward Arnold. But it doesn’t quite work. (This was Stewart’s first movie with Frank Capra.)

I think it’s because it tries too hard. It’s almost as if the movie senses something missing and therefore tries to mask it by pushing too much.

Jean Arthur plays the relatively level-headed member of a family of free-spirited oddballs, the Sycamores. At the head of their family is Grandpa, played by Lionel Barrymore, a man who long ago gave up the competitive rat-race most people are committed to in order to do whatever he feels like doing.

Everyone in the family follows his credo – they all do whatever makes them happy. The household is therefore chaotic – one daughter dances through the rooms, Arthur’s mother writes plays, someone’s husband makes music, while others make fireworks in the basement.

Everyone in the family follows his credo – they all do whatever makes them happy. The household is therefore chaotic – one daughter dances through the rooms, Arthur’s mother writes plays, someone’s husband makes music, while others make fireworks in the basement.

The household is wild and noisy.

Jean Arthur, the only family member who appears to actually work, meets Tony Kirby, played by Jimmy Stewart. They fall in love and want to marry. But Tony is the slightly rebellious son of parents who are straight-laced.

His father, Anthony P. Kirby (Edward Arnold) has little interest in anything other than making money. He’s the anti-thesis of the Sycamore’s Grandpa. His mother, Mrs. Anthony Kirby (Mary Forbes) is a social snob.

And that’s the film’s conflict and the source of its humour. The story is of how the Sycamore’s, who believe “you can’t take it with you,” win over the Kirby’s. (Well, Grandpa wins them over.)

And that’s the film’s conflict and the source of its humour. The story is of how the Sycamore’s, who believe “you can’t take it with you,” win over the Kirby’s. (Well, Grandpa wins them over.)

It’s very much a Capra theme and is played out in very Capra style.

But it doesn’t work well. The scenes in the Sycamore household are simply too excessive.

The movie tries too hard to make in chaotic and they become more annoying than amusing. The movie is also too long for the material. The main joke, the free-wheeling Sycamores, wears out quickly.

And while the lead performers are all very good, the supporting cast is a bit weak – less because of their performances than by the fact they have little to do except run around making noise.

And while the lead performers are all very good, the supporting cast is a bit weak – less because of their performances than by the fact they have little to do except run around making noise.

At best, the movie is only mildly entertaining, mildly funny. However, given the other movies Frank Capra was making around this time, he can be forgiven for having one that falls a bit flat.

And now, having said all that and having watched it again last night (February, 2011), I should point out how good Edward Arnold is in this movie. Really, the movie is all about his character. Scrooge-like (and a bit George Bailey-like), his character is the one that changes and it is his change that is at the heart of the movie. I found Arnold marvelous in this movie, very natural and also extremely funny at points (like the scene at the Sycamore’s home when he keeps sitting down in the awkward chair).

I liked the movie more this time but still feel it is a bit weak. But it’s worth it to see Edward Arnold.

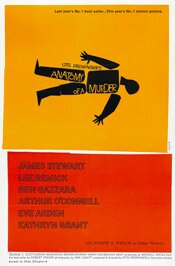

What I like about Anatomy of a Murder is that every so often a friend will say something like, “… This movie I saw on TV was so good …” As they describe it I realize what movie they mean and remark, “That’s Anatomy of a Murder.”

What I like about Anatomy of a Murder is that every so often a friend will say something like, “… This movie I saw on TV was so good …” As they describe it I realize what movie they mean and remark, “That’s Anatomy of a Murder.” Anatomy of a Murder (1959)

Anatomy of a Murder (1959)

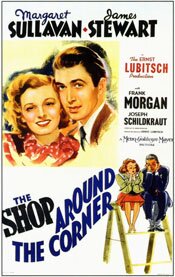

The Shop Around the Corner (1940)

The Shop Around the Corner (1940) The conceit of the film is pretty simple, which may be why it is such a template for other movies: Alfred (Jimmy Stewart) and Klara (Margaret Sullavan) have begun corresponding by letter as the result of Alfred stumbling across a classified ad Klara has put in the paper for a pen-pal. Both become enamoured of the person they think they are corresponding with.

The conceit of the film is pretty simple, which may be why it is such a template for other movies: Alfred (Jimmy Stewart) and Klara (Margaret Sullavan) have begun corresponding by letter as the result of Alfred stumbling across a classified ad Klara has put in the paper for a pen-pal. Both become enamoured of the person they think they are corresponding with. Margaret Sullavan is a terrific companion for him and the supporting cast, especially Frank Morgan (the Oz from The Wizard of Oz), are also brilliant.

Margaret Sullavan is a terrific companion for him and the supporting cast, especially Frank Morgan (the Oz from The Wizard of Oz), are also brilliant.