Mister Roberts is a much-loved movie so I always feel bad when I say that for me it’s just so-so. I kinda like it; I kinda don’t like. It may be due to not being much of a fan of either Henry Fonda or Jack Lemmon. (My mother loved Jack Lemmon.) I admire Fonda more than like him.

Subversive Preston Sturges and Morgan’s Creek

Eddie Bracken just looks funny. It’s not in a physically distorted way; it has something to do with the innocent, cherubic quality of his face that makes you smile. And when he starts moving? You start to laugh.

The curious hybrid called Deep Impact

When is a disaster movie not a disaster movie (even though it’s a disaster movie)? The answer is when it’s a Mimi Leder directed disaster movie and the usual trappings of the genre are downplayed and others, usually dealt with in an offhand manner, are lingered over.

High Sierra: When the bad guy is the good guy

I recently finished reading Stefan Kanfer’s Tough Without a Gun: The Life and Extraordinary Afterlife of Humphrey Bogart. (The title is from something Raymond Chandler said of Bogart.) So of course, I’m back to watching Bogart movies, at least for the time being.

Hereafter and the storytelling Clint Eastwood

You might think focusing on the story when making a movie would be a no-brainer but, as quite a few movies seem to illustrate, it’s not. One of things I’ve always liked about Clint Eastwood is his insistence on the story first, foremost, almost exclusively.

American Rebel: Eastwood bio a disappointing read

While I remember the song from Rawhide I don’t recall ever having seen it. For me, Clint Eastwood’s career would have begun with A Fistful of Dollars (1964).

The crazed and opulent Cleopatra

It’s appropriate that what I’ve written below about Cleopatra should be muddled as it is. That kind of reflects the movie. It’s a mess, in any number of ways, but what an arresting mess!

I’m pretty sure I saw this movie in the theatre when I was a kid and bits and pieces on TV over the years. I sat mesmerized through the entire movie about ten years ago when it came out on DVD. A week or so ago, however, I watched it again but this time it took me three days — I kept falling asleep on the couch. I suspect that was due to three things: 1) having seen it a few times already, 2) the sheer length of the movie and, 3) more wine than was wise.

As movies go, Cleopatra isn’t good or bad; it’s okay. But it’s probably the most fascinating “okay” movie you can see.

Continue reading

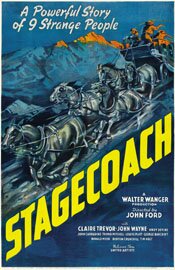

An imposing little Stagecoach from John Ford

When you think of how long it takes to make a movie today, at least a Hollywood movie, it’s quite astonishing to find John Ford cranked out three pretty extraordinary movies in 1939. His “go to” guys in that period were Henry Fonda and John Wayne. (In 1939-1940, he made five films — three with Fonda, two with Wayne.)

The number of movies isn’t the amazing part, though it is notable; what is remarkable is the quality of those films. (The movies are Stagecoach, Young Mr. Lincoln, Drums Along the Mohawk, The Grapes of Wrath and The Long Voyage Home.) For many, that creative glut would be a career. With Ford, some of his best films were still ahead of him.

Stagecoach (1939)

Stagecoach (1939)

Directed by John Ford

For what is essentially a simple western, Stagecoach is a pretty imposing little film. It’s daunting for all the film history associated with it, beginning with the introduction of John Wayne as movie star. (His first starring role was in Raoul Walsh’s 1930 movie The Big Trail. But it was John Ford and Stagecoach that made him a star.)

Interestingly, Wayne wasn’t the big star of Stagecoach. Claire Trevor was. She gets top billing and the movie is an ensemble piece, so no one character really dominates as they do in a “star vehicle.”

The movie also gave us Monument Valley, in Utah, which would afterward be forever associated with John Ford and be the quintessential “old West” landscape with its plateaus, mesas and buttes. And for many, this is the movie where Ford’s cinematic eye for people and landscapes — often low-angled shots; often sky dominated — is first seen.

There is one shot in particular that I loved. The upper two thirds of the frame is cloud fluffed sky. The lower third is plateau with a mesa off to the right; nothing but dessert otherwise, but for a trail with the lonely stagecoach winding along it from right to left, small and vulnerable.

The story is simple enough and one that is standard fare now: a group of people on their way from here to there, in this case on a stagecoach, encountering and overcoming various threats along the way.

In this movie, the threat comes from Geronimo as the stagecoach is passing through hostile Apache territory.

Riding the stage with the marshal (George Bancroft) are the “proper” lady, Lucy (Louise Platt) and the banker (Berton Churchill) … and a number of social outsiders. The hooker, the drunk, the outlaw … all with stronger moral codes than those who make up the proper society from which they’re excluded.

Both Dallas (the hooker) and the constantly inebriated Doc Boone (Thomas Mitchell) have been run out of town by self-appointed guardians of social mores.

Along the way, they meet up with the Ringo Kid (John Wayne), the outlaw. Though a disparate group and one at odds with itself, it is in working together that they make it to their destination.

As far as the story goes, the movie is nothing exceptional, at least not today. It’s significance is in what it means historically, as far as cinema goes, and John Ford’s directorial work.

Even though many of the things Ford did have since been copied and have become fairly common, the look of Stagecoach is still striking; more so when seen in its historical context.

For any serious lover of westerns, this movie is a must.

Apart from being at the start of an extraordinary string of westerns from John Ford that cover decades, it also gives us that moment when the camera moves in on John Wayne’s face announcing, in no uncertain terms, “Meet your favourite star for the next forty years.”

Yes, John Wayne was around for a long time after this movie came out. It should also be mentioned that simply as a movie, this is one very good film.

(In this same year, 1939, Ford would also direct Young Mr. Lincoln and Drums Along the Mohawk.)

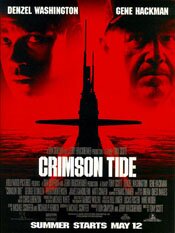

Characters in close quarters – Crimson Tide

You wouldn’t immediately associate submarine movies with a film like Key Largo but they have something in common. The dramatic tension comes about by having characters constrained within close quarters. In Key Largo, it’s within a hotel because of a hurricane; in submarine movies it’s due to the nature of submarines.

I don’t like a phrase like “submarine movies” but there is no getting around the fact there is a kind of sub-category of action-adventure films characterized by where they are set — on submarines. They’re often among the best of the action-adventure variety of films because of the close quarters that seem to force filmmakers to concentrate on characters.

Crimson Tide (1995)

Crimson Tide (1995)

Directed by Tony Scott

In the tradition of movies like Run Silent, Run Deep, The Hunt for Red October and Das Boot, the Tony Scott directed Crimson Tide is submarine drama with strong lead characters. If it distinguishes itself from those previous movies it is by being faster moving and much noisier.

That may not sound overly appealing but it be would wrong to think that way. This is a very good, very engaging action-adventure with a strong foundation: the performances of Denzel Washington and Gene Hackman.

It’s also supported by strong performances by its supporting cast – Matt Craven, George Dzundza, Viggo Mortensen and James Gandolfini, to name a few.

Without its strong cast, I think this would likely be just an average film but with them it is firmly anchored.

There is a state civil war in Russia. Rebel generals have taken over a base with nuclear weapons and it appears as if they may use them. The U.S. naval sub Alabama, nuclear-armed, is sent to Asian waters to await instructions. They get them: prepare your missiles. A further message, only partially received, may be orders to fire them or to stand down. It is unclear.

The movie’s conflict is between the sub’s captain (Gene Hackman) and its new executive officer (Denzel Washington). For the missiles to be fired, the two must be in agreement. They aren’t. The captain wants to fire; his second in command does not.

What makes movies like this dramatic and appealing (and you see this in films like Run Silent and Red October) is that the “bad guy” is external – off set. The leads, in this case Hackman and Washington, are both good guys but they are at opposing ends about what to do and thus in conflict.

This increases the film’s conflict by removing the easy, black and white choice and while an audiences’ sympathy may align with one, they can’t easily dismiss the other.

This is also reflected in the unfolding of the film’s drama where the sub’s crew must choose sides, many of whom are conflicted (like Mortensen’s Lt. Ince). We end up with struggles in the submarine, including mutiny, because of the lack of clarity. It’s all due to the ambiguity of the last orders received.

The movie doesn’t ease its audience into the story; it throws them in head first. Music and editing thrum as it begins with a journalist describing events in Russia. There is no slow unfolding of exposition. Director Scott and producer Jerry Bruckheimer take the approach of throwing the audience in at full speed. Details fly by like rapid fire flash cards.

In some movies, this is noise and fury approach can be a gimmick to mask an uninspired story but in Crimson Tide it’s a quick and effective way to get quickly to what is an intelligent, well told story. Perhaps its due to the close quarters of submarines, but movies like this seem to lend themselves to dramatic, character-driven films.

While my own preference is for the quieter tension of a movie like The Hunt for Red October (which I find more effective), it works for Crimson Tide as it delivers a compelling film that leaves an audience with something to question and discuss when is over.

On the whole, this is a very good movie and well worth seeing and more than once.