I love Stanley Kubrick but I hate his movies. Yes, hate is a bit strong. Let’s say dislike. I just find his films boring. At the same time, I find them visually brilliant and fascinating. I can’t think of any other director that leaves me with such a conflicted response.

Easy Living (1937): Everybody fall down

When a an expensive fur coat falls on her head, Mary Smith’s life of scraping together enough for food and rent turns upside down. She suddenly finds herself in a world of wealth, as she’s mistakenly perceived of as the mistress of Wall Street banker and tycoon, J.B. Ball.

Easy living was never so hard — or muddled and funny.

The strange love of movies – Cinema Paradiso

I last watched Cinema Paradiso about ten years ago. I’ve been meaning to watch it again for a long time but two things have held me back: the length (almost three hours — I don’t ever seem to have the time) and what I fear is a problem with my DVD copy. I hate the idea of getting halfway into a movie then finding a problem prevents me from seeing the rest.

But maybe this weekend I’ll overcome these hesitations. I really do want to see this again. For now, my impressions from when I saw it back around 2003 …

Cinema Paradiso (1988)

Cinema Paradiso (1988)

Directed by Giuseppe Tornatore

My memory is poor, so I really don’t recall the original, theatrical version of Cinema Paradiso. Whether or not the longer version I have (the 2003 DVD release) is better, I’ve no idea. It adds 51 minutes to the film – a 174 minute movie compared to the theatrical release at 123.

This version of Cinema Paradiso is broken into three parts – the main character Salvatore as a child, a young man, and finally as an older man (middle-aged). It begins with a kind of prologue of Salvatore as the older man.

The beautiful opening shot is almost still, like a photograph. Slowly the camera pulls back as the opening credits roll. As we pull back, the image we have is truly a filmmaker’s image: it’s very deliberately staged and framed, and I think we’re supposed to be aware of this. It is still, as if frozen, somewhat like the memories of the character Salvatore.

As the camera continues back, we become aware that we’re looking through a window. Slowly retreating, at one moment it almost looks like a film screen.

But once the credits are over and we’re at the furthest distance of the pull back, we see we’re in a room in a house. Dialogue begins and we see Salvatore’s mother move into the frame. The serene beauty of the opening shot, the staged nostalgic memory (which is what the opening has been) is disrupted by reality of everyday life.

But once the credits are over and we’re at the furthest distance of the pull back, we see we’re in a room in a house. Dialogue begins and we see Salvatore’s mother move into the frame. The serene beauty of the opening shot, the staged nostalgic memory (which is what the opening has been) is disrupted by reality of everyday life.

The current reality of this beginning (following the opening shot) establishes the kind of life Salvatore is living as a well-known filmmaker. It shows us a man avoiding his past. It gives us a man disconnected from his personal history and disconnected generally with the humanity around him. He’s isolated, and has chosen to be so.

The beginning also is what leads us into the story as it flashbacks to his life as a child, the film’s first section (following its prologue). It’s significant that we get into his childhood this way because it determines what we see and how we see it: it’s through the older Salvatore’s memory. It’s therefore not necessarily true in an objective sense.

This first part, Salvatore as a child (his memory of it), is generally brightly lit. It’s very open and spacious (compare the town square at the beginning of the film to the car-packed square at the end). In fact, everything here is open except for one thing: Alfredo’s little room in the Cinema Paradiso.

Alfredo, the projectionist at the town of Giancaldo’s movie theatre, the Cinema Paradiso, and who is the key figure in Salvatore’s life, is seemingly imprisoned. With the exception of a few scenes, we almost always see him looking through his window on the square, looking through the small opening in the projection room on the theatre, or loading and unloading reels of film in his cramped projection room. His life is contained by these small confines. He is always an observer. He is never a part of the audience below him in the theatre who seem to be continually chattering and interacting.

Alfredo, the projectionist at the town of Giancaldo’s movie theatre, the Cinema Paradiso, and who is the key figure in Salvatore’s life, is seemingly imprisoned. With the exception of a few scenes, we almost always see him looking through his window on the square, looking through the small opening in the projection room on the theatre, or loading and unloading reels of film in his cramped projection room. His life is contained by these small confines. He is always an observer. He is never a part of the audience below him in the theatre who seem to be continually chattering and interacting.

Like an image on film limited by the frames, his world is constrained by the walls of his projection room. But as the movie’s opening has shown us, and as demonstrated in Sergio Leone’s The Good, The Bad and the Ugly, there is a world beyond the image’s frame (Tori’s mother in the movie’s opening). However much they may delight, or how real they may seem, movie’s are not everything. There is a world beyond them.

In the second part of the movie, Salvatore begins to become like Alfredo, at least this is a choice he is presented with. He takes over the projection booth. But he does have a choice and this is what the second part concerns.

While isolated in the projection booth, he also has a foot in the more tactile and chaotic world of the audience. This is through his relationship with the young woman Elena. In this part of the film, director Guiseppe Tornatore introduces a sexual element – in the films seen in the Cinema Paradiso, in the behavior of the boys of Salvatore’s age, and in Salvatore’s relationship with Elena, though this latter is more romantic in its treatment than sexual.

But the purpose of the sexuality is its relationship to romance and personal connections. It is something that pulls Salvatore away from the isolated world of films into the community of the audience, the town.

Alfredo, knowing this, and sensing the cinematic artist in Salvatore, undermines the relationship between Salvatore and Elena. This action parallels that of the town’s priest who in the first part of the film had been ordering the censoring of all the scenes involving kisses, scenes that suggested intimacy.

Alfredo, knowing this, and sensing the cinematic artist in Salvatore, undermines the relationship between Salvatore and Elena. This action parallels that of the town’s priest who in the first part of the film had been ordering the censoring of all the scenes involving kisses, scenes that suggested intimacy.

Salvatore’s relationship with Elena no longer a possibility, he now leaves the town (the audience). Alfredo not only supports this decision, he prompts it. He tells Salvatore, “You have to go away for a long time, many years, before you can come back and find your people.”

It’s ironic that Alfredo says this as he has never gone away, at least not physically. It could, however, be argued he has left emotionally and spiritually and has yet to return.

This leads to the film’s third part, the movie’s “now.” The older Salvatore finally returns to the town of Giancaldo. He returns for Alfredo’s funeral (who, in a sense, is finally “going away”). For Salvatore, the return is a series of revelations. As he says himself, he has been afraid to return.

One of his biggest discoveries is of Alfredo’s manipulations to keep Salvatore and Elena apart. She did not betray Salvatore, nor he her. It was Alfredo. His reasons were to force Salvatore out to his career as an artist, a famous filmmaker.

The other revelation is the film’s conclusion where Salvatore sits alone in the theatre watching Alfredo’s final gift, a reel of film. It is all the kisses and other intimate moments of human relationships the priest had removed from the movies. It is as if Alfredo is trying to return the part of life he had removed from Alfredo.

In contrast to the film’s beginning, this final section is visually darker and cramped. It is the real part of the film, as opposed to the remembered.

In this final part, we also see the destruction of the theatre, the Cinema Paradiso. While not the destruction of movies, it seems it’s the destruction of the tyranny of fantasy. While painful, it frees Salvatore from the confines imposed by images. It frees him of the prison art imposes and allows him back into life. We see a shot of young people laughing with a youthful sense of fun as they see the destruction of the building. It’s as if the present is clearing away the past so it can live.

The film appears to have two meanings, or at least two intents. In part, it is a loving homage to cinema and what it gives us. At the same time, it is also about the tyranny of art, at least for the artist. It is about what is denied him or her in order to pursue their art. It seems to say, as an artist you can observe life but you cannot be a part of it. You must remain a step removed. And movies are not real. They are moments; they are memories.

I think the film, at least in its extended version, is less a film about a love of cinema than a film about the sacrifices demanded by art. And while it does not provide an answer, I think it also speculates on the relationship between life and art and which has greater value.

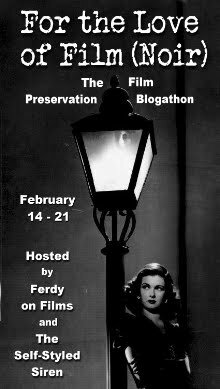

The accidental film noir: I Wake Up Screaming

It’s Day 2 of For the Love of Film (Noir) — don’t forget to (or use the button on the right). Today I have a quickly scribbled, un-proofed, un-thought through look at the movie I watched last night. The studio considered calling it Hot Spot but, according to the DVD I have, the actors insisted on them using the original name, which is …

I Wake Up Screaming (1941)

Directed by H. Bruce Humberstone

As I watched I Wake Up Screaming last night I had two thoughts running concurrently. First, this should not be a good movie. Second, somehow it manages to be a good movie. How does that happen?

I’m not sure. I think it lies partly in Betty Grable, whose performance is a level above the other main actors in the movie.

It’s also in the characterization of Ed Cornell, played by Laird Cregar, who seems a cross between Vincent Price (in the slightly effeminate voice and its cadence) and possibly a low rent version of George Sand. (I mean vocally, nothing else, and not much there either. But there seems to be something vaguely Sand-ish in the voice.)

Cregar’s Cornell is creepy, to say the least, and that makes the movie compelling. Though the film’s mystery may be obvious, it doesn’t matter. The creepiness keeps us fascinated in a “slowing down to view the accident” kind of way. Cregar’s character isn’t the only one that gives us the willies.

Elisha Cook Jr.’s Harry is equally troubling. Soft-spoken and gentle, his focus and attentiveness to Grable’s Jill Lynn leaves us feeling something isn’t right about him. He’s stalker material.

Much of what makes the movie watchable is in the script. The bad guys in this movie – and there are a lot of them – are not villains so much in the commitment of crimes regard, as in their psychology. In fact, most of them have stalker-like personalities or variants of it.

They are all focused in some way on Vicky Lynn, played by Carole Landis. They want to either possess her, use her, or both. And she, being ambitious, is happy to permit it as she uses them. Thus, in a sense, she invites what follows from it.

Into this morass of twisted personalities come Victor Mature as Frankie, a kind of nice if goofy sports promoter (who find himself accused of murder) and Vicky’s sister, Grable’s Jill Lynn.

Frankie and Jill are the normal ones (for lack of a better word) and also the ones who suffer the consequences of a world populated by twisted personalities.

Visually, the movie delivers the noir goods but that may be less an aesthetic decision as a kneejerk response to making a crime movie in the forties. Crime equals scenes of darkness and shadow, ergo scenes of darkness and shadow. I get the sense director H. Bruce Humberstone was a paint-by-numbers kind of director, though that may be unfair to him. But that is how it strikes me.

Still, by accident or design, the movie looks good as a noir. It has a low budget feel and some very nice shots, especially near the end where we see Mature looking down at Harry snoozing at the front desk.

Overall, then, I Wake Up Screaming strikes me as an accidental noir. It discovers a noir world in the script it brings to the screen and in the kind of kneejerk response of how it visually portrays that script.

Much of what happens on screen is highly melodramatic and it would be too much were it not for the material driving it, Laird’s unsettling Cornell, and Grable’s much better anchored performance as Jill. Victor Mature looks great as a noir character, especially in the interrogation scenes, but he is often well over-the-top. Also, for about two thirds of the movie, once outside the interrogation room (and often within it) he plays a goofy kind of guy without a care in the world. It’s deliberate, in part, as it’s an aspect of the character. But it just seems too much.

And having gone on with all these negative comments about the movie, I still have to say I liked it quite a bit. However, it feels to me it’s a good movie through dumb luck; a film noir by accident.

Film noir and film preservation

If we actually lived in a film noir world, there would be a certain futility in trying to preserve a movie. What would be the point? Nothing lasts; everything dies. It’s all hopeless … in a film noir world.

If we actually lived in a film noir world, there would be a certain futility in trying to preserve a movie. What would be the point? Nothing lasts; everything dies. It’s all hopeless … in a film noir world.

Fortunately the real world differs considerably from how we choose to see it — be it through the eyes of a Fritz Lang or a Walt Disney. That’s also why I remind you (as if anyone who likes movies needs reminding) that in a little over a week the For The Love of Film (Noir) blogathon gets underway. It runs February 14 to 21 and I’ll be taking part by tossing up a few posts. I suspect I’ll be the blogger least informed on the subject but I sort of like that idea.

There’s a nice opportunity to learn more.

I can say this about what makes this blogathon particularly fascinating to me (apart from the film preservation aspect): I’ll find it intriguing to see what some people consider film noir. Like most genre terms, be they applied to movies or something else, there is an aspect of subjectivity that smudges lines and makes things difficult to grasp the more closely you look at them.

I can think of one movie from 2003 that I think of as noir but I want to watch it again and see if I still think so (I need to get the DVD back from a friend). If I still think of it as noir, I’ll be curious to see if anyone else does.

Another movie I’d like to watch and possibly re-do what I wrote a few years ago is Kiss Me Deadly, a movie I absolutely hated when I first watched it. Because I reacted so strongly the first time, in the negative sense, I find it difficult to persuade myself to re-watch. I hope I can because it makes for another interesting question: when cynicism becomes nihilism, is it still film noir or does it become a parody of the genre?

I suppose that depends on how you define noir. Is it mood? Story? Lighting? Direction? Is it just snappy Raymond Chandler-like dialogue and guys wearing fedoras?

I hope we can find out in a little over a week!

Four movies and a post

Over this holiday period, while I haven’t been posting on any of my sites, neither have I been sitting still.

Over this holiday period, while I haven’t been posting on any of my sites, neither have I been sitting still.

Here on Piddleville, I actually have been adding reviews, though not highlighting them on the home page here.

I hope to rectify that today. So, recently seen …

Holiday Inn (1942)

The movie Holiday Inn is memorable for a number of things, some good, some not so good. To begin with, it brings together a trio made up of Irving Berlin, Bing Crosby and Fred Astaire. Not a bad place to start. The movie itself is a Hollywood soufflé, very light, very unlikely, and quite delightful…

Read more

Unbreakable (2002)

Movies with surprise endings don’t often work well and, even when they do, it’s easy to tire of them quickly. In a sense, they are gimmicky. Done rarely, they’re riveting; done often, they’re tedious. I think M. Night Shyamalan knows this and feels the same way … You get the sense as you watch Unbreakable that he was trying to avoid the surprise ending. On the other hand, you also get the sense that stories of that kind are his natural inclination…

Read more

The Bells of St. Mary’s (1945)

The Bells of St. Mary’s is movie that is very representative of a type of movie Hollywood made in its heyday, very much the way it’s predecessor was, Going My Way. On one hand, it is a type of film that Hollywood has continued to make (like certain Disney films) with varying degrees of success – family oriented and sentimental. On the other hand, it is anachronistic and, for some, nostalgic…

Read more

Now, Voyager (1942)

Here’s a movie that caught me by surprise. It’s another one of those films I went into with little or no expectations. In fact, if anything, I expected it to be a dud. (I had seen a number of older, black and white turkeys recently.) Now, Voyager was wonderful. It’s also an unapologetic soap opera, the kind Hollywood once did so well…

Read more

And now you are up to date. Sort of. More or less. My memory isn’t great; I may have have forgotten something …

Familiarity: a characteristic of the comfort movie?

A friend of mine went to visit some friends in Edmonton a few months ago. When she returned, I asked her what she had done. “Nothing,” she said.

“Did you go anywhere?”

“Nope.”

“Did you at least go to that restaurant I told you about?”

“No; there wasn’t time.”

She had been there for over a week. Yet all she had done was spend time with her friends.

That’s what some comfort movies are.

Many years ago when the marathon-like M*A*S*H was finally ending its time on television, someone made the observation that few people had watched it because they were eager to see the next episode. They weren’t wondering what would happen next. They were watching simply because they wanted to spend time with the characters they had come to know so well.

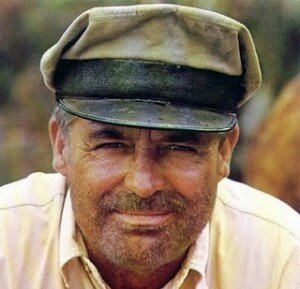

That is what some comfort movies do. Many of the John Wayne movies are like this. They may have drama or comedy but many people watch them simply to spend time with their idea of John Wayne and the characters associated with him.

This particularly comes across in his later movies, like Hatari! or Donovan’s Reef, or even an earlier movie like The Quiet Man. Their merits as films aside, people watch to see the Duke and the actors/characters associated with him, like Maureen O’Hara. There is a sense of knowing them, of a personal relationship, though we know that couldn’t possibly be true – we’ve never even met them! Yet we feel that way.

So it strikes me that a characteristic of comfort movies is familiarity. We revisit certain movies in the same way we revisit certain friends and family. Familiarity. We enjoy spending time with them. This is why they are comfort movies.

So it strikes me that a characteristic of comfort movies is familiarity. We revisit certain movies in the same way we revisit certain friends and family. Familiarity. We enjoy spending time with them. This is why they are comfort movies.

Although it’s not the movie I’d like to start off with (it’s a bit misleading as far as what I consider a comfort movie to be), my favourite movie as far as this category goes is Father Goose.

Gasp! Am I nuts? Possibly. But for me this movie is as comfortable as old slippers. And that may be a good analogy because this movie is probably just as fashionable. Besides, it stars the always familiar Cary Grant, whom many simply like to watch. In anything.

- Review: Father Goose 1964

Comfort movies — what are they?

I often refer to certain films as comfort movies. I think I started using this term because my lingering wannabe cinema buff always felt a bit embarrassed at liking some movies. The term is a variation on the phrase “guilty pleasure” but a bit more specific, though I may not be able to articulate well what I mean by it.

In some ways, it’s best defined by what it is not. A comfort movie isn’t challenging. It seldom has lofty artistic aspirations; usually, it simply wants to entertain. Comfort movies, for the most part, aren’t dark, though they may have dark aspects to them, to varying degrees. (After all, there is no drama without some dark element.)

Possibly the best known example of a comfort movie (though it isn’t that for me) is It’s A Wonderful Life. People watch this movie over and over. It’s hard to miss, mind you, because it’s on TV repeatedly in the holiday season. It’s a movie with darkness, quite a bit of it actually, yet its big Norman Rockwell-like finish makes us feel so good we watch it again next year.

Off the top of my head, I can’t think of a single comfort movie that doesn’t have a happy ending, though sometimes it’s a bit equivocated. A happy ending may be a defining characteristic of the comfort movie.

By contrast, there is a movie like The Godfather. It may be my favourite movie of all time (it’s not) and it may be my standard of what a film should be and do, but it’s not a comfort movie. You don’t watch The Godfather because it makes you feel good; not in the sense I mean. You don’t remember it for a happy ending or sense of elation.

I’ve decided I’m going to make a personal list of comfort movies. This may help me get closer to a more clear definition of what I intuitively know is a comfort movie.

I’m going to list twenty of them. This assumes that I can come up with twenty. I think I can, so very shortly I’m going to start putting them up on Piddleville.

(After reading this over, I think I’ll probably disagree with it as I start my making my list. I was just going over some of the movies I would put on it and realized two things: 1) quite a few of them are at odds with my attempted definition, and 2) a change in cinema and sensibilities in about the 1970’s redefined what I think of as a comfort movie. So as usual I’m full of hooey.)

Also see:

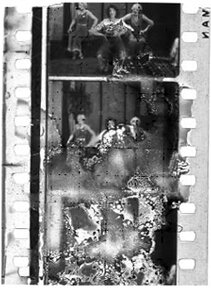

Film preservation in Dawson City

In 1978 a startling discovery elated the small world of film preservationists, restorers, and scholars. A trove of long lost original nitrate copies of silent movies was uncovered at a construction site in Dawson City, Alaska. Among them were long lost films starring Pearl White, Harold Lloyd, Douglas Fairbanks, and Lon Chaney. The permafrost had preserved them for 50 years after they had been tossed into an empty, abandoned swimming pool and covered with fill dirt.

How did these cinema treasures get to Dawson City? The story says a lot about the path of film preservation. Dawson City, it turns out, is at the end of the movie theater print circuit. Prints are usually shipped from theater to theater in an unchanging pattern. A new print starts in a big city like Seattle. From there it might go to Spokane, and then to Bellingham; next on the list might be Fairbanks, then Nome and finally Dawson City.

By the time a print arrives in Dawson City it has been run through a couple dozen grinding projectors by gum chewing teenage projectionists. It has been broken, spliced, cut to insert trailers and re-spliced and re-broken. It has so many scratches the Dawson City audience probably thinks it is always raining in the lower 48.

When a print ends its run in Dawson City it’s not worth shipping back. At first, the local movie theater donated the prints to the library. But in 1929 the library decided they didn’t want a lot of highly flammable nitrate prints in their stacks. They heaved them into an abandoned swimming pool where they were used as fill trash.

Trash: that’s the secret of film preservation. The great find of 1978 happened because somebody was digging a new foundation and unearthed a movie burial ground. The permafrost layer in the fill dirt above the movies had preserved them as good as in a temperature-controlled vault. They were given to the Library of Congress and restored.

Many assumed-lost movies have been found this way. They turn up in Uncle George’s attic or in Grandma’s garage. Movie making has always been a seat-of-the-pants occupation balanced between tight budgets and the rush to make money. Studios rarely kept archive prints. It was just another expense nobody wanted to pay for.

And why bother? The film negative was stored in the lab vault under lock and key and temperature control. That is, if the producer paid the rent and sprinkler pipes didn’t break and flood. Hollywood pros speak the name Roger Mayer with reverence. He was in charge of the lab at MGM and one of the first people to realize the tremendous value of carefully preserved movies. He convinced the studio to let him reprint many old ones on modern film stock. Before celluloid replaced nitrate as the base on which moving pictures were photographed, even carefully stored movies could turn to dust.

Every film student knows the story of Robert Flaherty traversing the Arctic making his famous documentary, Nanook of the North. After a year of shooting, he gathered all the film in his cutting room to edit and lit a cigarette. Poof! In 30 seconds everything was gone (Flaherty went back a second time and reshot the film).

Once missing films are found, the science and art of film restoration takes over. The caisson where most of this happens is an underground labyrinth at the Eastman House of Photography, in Rochester, NY. (There’s no reason it is underground except George Eastman’s old mansion is on top of it). Technicians have special machines for cleaning, lubricating, and printing. Old images are not the only problem. Film shrinks over time and will not fit the sprocket gears of newer machines. Restorers are crafty folks who know secret tricks like wet gate printing and high resolution video manipulation. Sometimes they must restore one frame at a time. They are true alchemists.

The next time you see Marty Scorsese on TV standing at one of those black tie parties announcing a brand new print of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, think of Dawson City, The Eastman House, and all those people who knew enough to read the labels on the cans before cleaning out Grandma’s garage.

(A big thank you goes out to for today’s guest post. You’ll find him over at Movie With Me where I – Bill – am an occasional contributor. Here is how Roberto describes himself at Movie With Me: “Resident Curmudgeon & Film Buff

“As a long time Hollywood producer, I love the internet because there are no rules, no gatekeepers, no stupid executives whose only skill is looking good in a suit. And I love film. The ones that are great, and the ones not-so-great that have moments of inspiration or brilliance. Making a movie is a roll of the dice. Once you have actors and tempers and weather you never know what will happen. The only thing you can be sure of is it will never turn out exactly the way you planned. I salute anyone who tries, and I try to sing the unsung because they too deserve a little glory for attempting the impossible. “

Many, many thanks!)