It’s hard to think of John Wayne and romance at the same time. The image of one and the image of the other don’t rest well side by side; one seems to negate the other.

Is Hondo the definitive John Wayne movie?

I don’t thing many people would argue that Hondo is the best of John Wayne’s movies. Similarly, I don’t many will argue against it being among his best both as a western and as a performance from Wayne. But if ever there was a movie that illustrated what John Wayne did onscreen, how he came across and essentially provided a definition for those words “John Wayne,” it’s Hondo.

The great and debatable Red River

I really go on a ramble here about this movie, though it is more a ramble about John Wayne’s acting and speech pattern than the film. This is considered one of the great westerns by many and I would be among them. However, while I like Wayne in it and think it’s one of his best roles, it is not my favourite John Wayne performance.

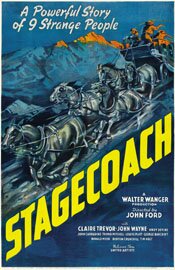

An imposing little Stagecoach from John Ford

When you think of how long it takes to make a movie today, at least a Hollywood movie, it’s quite astonishing to find John Ford cranked out three pretty extraordinary movies in 1939. His “go to” guys in that period were Henry Fonda and John Wayne. (In 1939-1940, he made five films — three with Fonda, two with Wayne.)

The number of movies isn’t the amazing part, though it is notable; what is remarkable is the quality of those films. (The movies are Stagecoach, Young Mr. Lincoln, Drums Along the Mohawk, The Grapes of Wrath and The Long Voyage Home.) For many, that creative glut would be a career. With Ford, some of his best films were still ahead of him.

Stagecoach (1939)

Stagecoach (1939)

Directed by John Ford

For what is essentially a simple western, Stagecoach is a pretty imposing little film. It’s daunting for all the film history associated with it, beginning with the introduction of John Wayne as movie star. (His first starring role was in Raoul Walsh’s 1930 movie The Big Trail. But it was John Ford and Stagecoach that made him a star.)

Interestingly, Wayne wasn’t the big star of Stagecoach. Claire Trevor was. She gets top billing and the movie is an ensemble piece, so no one character really dominates as they do in a “star vehicle.”

The movie also gave us Monument Valley, in Utah, which would afterward be forever associated with John Ford and be the quintessential “old West” landscape with its plateaus, mesas and buttes. And for many, this is the movie where Ford’s cinematic eye for people and landscapes — often low-angled shots; often sky dominated — is first seen.

There is one shot in particular that I loved. The upper two thirds of the frame is cloud fluffed sky. The lower third is plateau with a mesa off to the right; nothing but dessert otherwise, but for a trail with the lonely stagecoach winding along it from right to left, small and vulnerable.

The story is simple enough and one that is standard fare now: a group of people on their way from here to there, in this case on a stagecoach, encountering and overcoming various threats along the way.

In this movie, the threat comes from Geronimo as the stagecoach is passing through hostile Apache territory.

Riding the stage with the marshal (George Bancroft) are the “proper” lady, Lucy (Louise Platt) and the banker (Berton Churchill) … and a number of social outsiders. The hooker, the drunk, the outlaw … all with stronger moral codes than those who make up the proper society from which they’re excluded.

Both Dallas (the hooker) and the constantly inebriated Doc Boone (Thomas Mitchell) have been run out of town by self-appointed guardians of social mores.

Along the way, they meet up with the Ringo Kid (John Wayne), the outlaw. Though a disparate group and one at odds with itself, it is in working together that they make it to their destination.

As far as the story goes, the movie is nothing exceptional, at least not today. It’s significance is in what it means historically, as far as cinema goes, and John Ford’s directorial work.

Even though many of the things Ford did have since been copied and have become fairly common, the look of Stagecoach is still striking; more so when seen in its historical context.

For any serious lover of westerns, this movie is a must.

Apart from being at the start of an extraordinary string of westerns from John Ford that cover decades, it also gives us that moment when the camera moves in on John Wayne’s face announcing, in no uncertain terms, “Meet your favourite star for the next forty years.”

Yes, John Wayne was around for a long time after this movie came out. It should also be mentioned that simply as a movie, this is one very good film.

(In this same year, 1939, Ford would also direct Young Mr. Lincoln and Drums Along the Mohawk.)

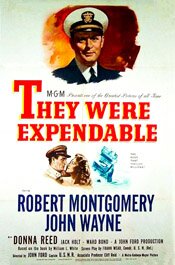

John Ford, John Wayne and Expendable

Sometimes the release dates of movies can be significant. Get it wrong and you’re all in a muddle, as I was when I watched They Were Expendable.

The movie itself isn’t anything I would say you should rush out to see unless you’re a really big John Ford and/or John Wayne fan. The tone of it is curious, however, given the kind of movie it is and what it is about. Some movies are intriguing despite not being great films and that is the case with this one.

They Were Expendable (1945)

They Were Expendable (1945)

Directed by John Ford

I was very confused when I watched the war movie They Were Expendable because I thought it was from 1941. It turns out that is when the movie is set as it opens. My confusion evaporated, however, when I realized it was from 1945, though it is still an unusual movie that John Ford gives us.

Believe me, with this movie the year really matters – especially if you confuse it with four years earlier.

This movie was released in December of 1945. In World War II, Japan formally surrendered in September of 1945.

The movie is somber recounting of the early days of the war for the U.S., beginning with the attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941.

Made with the approval and assistance of the U.S. Navy, Army and Coast Guard, it shows us the U.S. getting its behind kicked by the Japanese – starting in Pearl Harbor and continuing through the Philippines.

Audiences at the time of the film’s release, however, would be fully and completely aware of the end result of it all – victory in the Pacific; Japan’s surrender.

The reason John Ford shows us all the bad news from the war’s early days is because he’s telling the story of the PT boats – how their role in the war came about (they weren’t highly regarded originally), how they won respect and the sacrifices made by the crews that worked them. (The tagline was, “A tribute to those who did so much… with so little!”) However, the main character is really the boat itself.

The movie is a solemn tribute and sober homage but also full of patriotism which, appropriate to the period of its release, may strike a current day viewer as a bit much.

There are good action scenes in the movie as well as some interesting, almost noir-ish lighting in others. The movie itself appears to be in poor shape, at least on the DVD copy I have. I don’t know if any restorative work went into it but it doesn’t appear so given the scratches in a number of scenes. I’m a bit surprised it comes to use from Warner Brothers. It may have something to do with the lack of good original film materials. I don’t know.

Overall, I can’t say this is a great movie. It’s a curious one, however. It’s worth seeing at least once, especially if you’re a fan of either John Ford or John Wayne. Just keep in mind this movie should probably be viewed as a propaganda work.

And maybe that is what makes it peculiar. It’s quite a bit of “Rah, rah!” about PT boats but seems to also want to be a solid drama and thus it acquires a bipolar quality.

Familiarity: a characteristic of the comfort movie?

A friend of mine went to visit some friends in Edmonton a few months ago. When she returned, I asked her what she had done. “Nothing,” she said.

“Did you go anywhere?”

“Nope.”

“Did you at least go to that restaurant I told you about?”

“No; there wasn’t time.”

She had been there for over a week. Yet all she had done was spend time with her friends.

That’s what some comfort movies are.

Many years ago when the marathon-like M*A*S*H was finally ending its time on television, someone made the observation that few people had watched it because they were eager to see the next episode. They weren’t wondering what would happen next. They were watching simply because they wanted to spend time with the characters they had come to know so well.

That is what some comfort movies do. Many of the John Wayne movies are like this. They may have drama or comedy but many people watch them simply to spend time with their idea of John Wayne and the characters associated with him.

This particularly comes across in his later movies, like Hatari! or Donovan’s Reef, or even an earlier movie like The Quiet Man. Their merits as films aside, people watch to see the Duke and the actors/characters associated with him, like Maureen O’Hara. There is a sense of knowing them, of a personal relationship, though we know that couldn’t possibly be true – we’ve never even met them! Yet we feel that way.

So it strikes me that a characteristic of comfort movies is familiarity. We revisit certain movies in the same way we revisit certain friends and family. Familiarity. We enjoy spending time with them. This is why they are comfort movies.

So it strikes me that a characteristic of comfort movies is familiarity. We revisit certain movies in the same way we revisit certain friends and family. Familiarity. We enjoy spending time with them. This is why they are comfort movies.

Although it’s not the movie I’d like to start off with (it’s a bit misleading as far as what I consider a comfort movie to be), my favourite movie as far as this category goes is Father Goose.

Gasp! Am I nuts? Possibly. But for me this movie is as comfortable as old slippers. And that may be a good analogy because this movie is probably just as fashionable. Besides, it stars the always familiar Cary Grant, whom many simply like to watch. In anything.

- Review: Father Goose 1964

20 movies: Tombstone (1993)

I can think of no better place to start my list of twenty movies than with one of my favourite kinds of movies, the western, and specifically one of my favourite westerns, Tombstone from 1993. If you want something to watch this summer, try this one.

While there are many aspects to the movie that are excellent, the one that truly stands out is Val Kilmer’s portrayal of Doc Holliday. If you have never seen the movie, or if you haven’t seen it in a few years, it’s time to watch one of the great performances. In some ways, Tombstone is a variation of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and Kilmer’s Holliday is a new take on John Wayne’s Tom Doniphon.

Here’s my review of the movie that I wrote a few years ago:

Tombstone

directed by George P. Cosmatos

This movie frustrates me because I don’t know what to write. It’s one of the best westerns I’ve ever seen and, to be truthful, that’s really all I have to say about it.

Of course, I love westerns. But I’m not sure why. I think it’s because of the simplicity of the stories and the fact that they are, essentially, all mythical.

I suppose you could say this about all movies but westerns, in particular, access mythic elements and use them to engage us. They really are the same damn story played over and over again.

The best westerns do this; the least successful ones try to play with the genre.

Having said that, I think director George P. Cosmatos and writer Kevin Jarre do play with the genre just a tad … but they rigidly adhere to the essential elements. For example, one of the staples of westerns is the opening when the bad guys come in and do something really, really bad. I can’t think of a single Clint Eastwood western that doesn’t do this. What this does is immediately set the context of the movie – a wild and lawless landscape that is crying out for order.

The next step is to introduce us to the good guy (or guys) who are reluctantly drawn in and eventually save the day.

Simple stuff, and exactly what Tombstone does.

But within this simple framework, Cosmatos and Jarre do much more. Chiefly, they give us characters with much greater delineation and far more contradictions that the average B western.

In particular, we get the incredible performance of Val Kilmer as Doc Holliday. It’s not the usual Doc Holliday; this one is true to history and, within that, Kilmer gives us perfect and unexpected nuances.

And while the Doc Holliday character may be the one we walk away remembering best, Kurt Russell’s Wyatt Earp is equally masterful. He’s less interesting only because his character is the good guy. But he has his own contradictions and, more importantly, it’s the apparent paradox of his relationship with Doc Holliday around which the movie revolves and succeeds.

There are, of course, a few minor problems with the film, as with all movies. For example, there is the scene when Bill Paxton as the youngest Earp, Morgan, is shot and Kurt Russell is with him. Russell’s hands and arms are covered in blood. He runs his hands over Paxton’s forehead – he seems to touch just about everyone in the place, including himself – yet no blood rubs off on anyone. Huh? How’d that happen?

But it’s a quibble. The movie is pure western, from setting to music to story. It also avoids that sepia nonsense so many westerns have. Rather, they have shot this movie to show the colour of the mythic west and it’s a tremendous relief to see a western with this much confidence in itself as a western.

Tombstone (the trailer)

Jean Arthur and John Wayne

After having it on my computer for about two months in a half-finished state, I’ve finally posted my take on A Lady Takes a Chance (1943). It stars Jean Arthur and John Wayne and, yes, it’s a romantic comedy.

It’s not, however, the best romantic comedy. It’s pretty mediocre. However, both Arthur and Wayne are wonderful, each in their own way.

If you are a fan of either actor, you should see this one. The film, as a whole, is pleasant but not anything that would have change the world of cinema. My review can be found here.

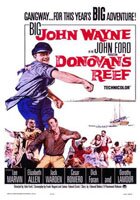

Donovan’s Reef: Fisticuffs anyone?

I took a shot at assessing another John Wayne movie (since I’d been doing quite a few of those lately). Here’s what I came up with:

Donovan’s Reef (1963)

This is a difficult film to defend, much less recommend, for many reasons, most of which have to do with director John Ford. Still, if I may refer to Glenn Erickson who, in his review, refers to Andrew Sarris in The American Cinema, “…Donovan’s Reef was like some kind of heaven that Tom Doniphon and Liberty Valance, both fun-loving uncivilized types, had retreated to in the afterlife. And it’s the key to appreciating this broad comedy.”

This is a difficult film to defend, much less recommend, for many reasons, most of which have to do with director John Ford. Still, if I may refer to Glenn Erickson who, in his review, refers to Andrew Sarris in The American Cinema, “…Donovan’s Reef was like some kind of heaven that Tom Doniphon and Liberty Valance, both fun-loving uncivilized types, had retreated to in the afterlife. And it’s the key to appreciating this broad comedy.”

In other words, Donovan’s Reef is fantasy. It also recapitulates many of the themes and sentiments that characterize the John Ford canon. You could call it a kind of executive summary. Unfortunately, many of those themes and sentiments are more than a little disagreeable, even offensive, to a modern sensibility, like the racial and gender characterizations.

Compounding that is the structure and style of the film which is somewhat clunky. I think Erickson describes it pretty well when he writes that it is, “…a surreal, almost abstract progression of kabuki-like rituals from the world of John Ford.”

The movie comes across as a collection of set pieces that are only loosely tied together. It’s almost episodic. These set pieces, however, are like a highlighting of key aspects of Ford’s work – again, almost like an executive summary. Many of these conclude with brawls – many of them seem to be excuses for brawl scenes – fights that involve almost everyone and where no one gets hurt.

The movie comes across as a collection of set pieces that are only loosely tied together. It’s almost episodic. These set pieces, however, are like a highlighting of key aspects of Ford’s work – again, almost like an executive summary. Many of these conclude with brawls – many of them seem to be excuses for brawl scenes – fights that involve almost everyone and where no one gets hurt.

It’s all set in an idyllic, mythical South Seas world called Haleakaloa. It stars John Wayne and Lee Marvin as two brawling pals who like drinking and fighting, and being their own men. There is a romance that reiterates Ford’s vision of relationships between men – antagonistic, but in a charming way.

But is it a good movie? I would have to say no even though I did enjoy it. Despite the similarity to North to Alaska, the film it most reminds me of is Hatari! That movie, directed by Howard Hawks, is long and meandering. It seems to be more about spending time with the characters. This how Donovan’s Reef strikes me. The story is flimsy at best. The movie is more about spending time with Wayne, Marvin and, in behind the scenes, Ford in a fantasy paradise. It’s almost like sitting around with old friends and having a few beers.

This is why I can enjoy the movie. If you’re familiar with Ford/Wayne movies, if you grew up with them and liked them, you can enjoy the movie, though you couldn’t credibly argue for it being a “good” movie. At least, I don’t think so.

And if you didn’t grow up with these guys, if you’re unfamiliar with the sensibility and are unwilling to turn a blind eye to some of the stereotyping and so on (rather like sitting down with a politically incorrect grandfather who, smiling, unthinkingly throws out inappropriate remarks) … No, you won’t like this movie.

And if you didn’t grow up with these guys, if you’re unfamiliar with the sensibility and are unwilling to turn a blind eye to some of the stereotyping and so on (rather like sitting down with a politically incorrect grandfather who, smiling, unthinkingly throws out inappropriate remarks) … No, you won’t like this movie.

But then, the movie was never made for you. It’s more like a greeting card sent to old friends from Ford, full of the John Ford “stuff,” from the characters to the scenes.

1½ stars out of 4.