I think I’m one of the few people who doesn’t care much for Out of the Past. It may be that for me the closer a movie gets to film noir, the less it appeals to me. I can’t argue with any of the superlatives used to describe this one. But despite all it does right in terms of noir, I can’t get terribly enthused.

Reacquainted with Myrna Loy and William Powell

Last week I went on a run of watching and writing about some Myrna Loy and William Powell movies I have in my collection. I went through four five of them, three four of which I’ve had here, unwatched, for about five years.

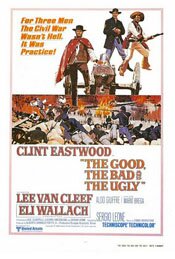

Sergio Leone and a good, odd western

I’m currently reading Marc Eliot’s Clint Eastwood: American Rebel and it inevitably got me thinking about the earlier Eastwood movies, the spaghetti westerns, including The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Below is my lengthy rambling about it from quite a while ago (2000?). For what it is worth …

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

Directed by Sergio Leone

One of the best, and oddest, westerns ever made is The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo). It’s hard to imagine anyone making a movie like this today. It’s too long (it would be argued). Some of the scenes, even shots, are too long. Gee, it takes 30 minutes to introduce the three primary characters. What’s that about?

Continue reading

20 movies: The Big Heat (1953)

Depending on your age, you may remember seeing Glenn Ford in movies and on television. I’m thinking roughly of the 1970’s, perhaps late 60’s. He usually had an avuncular quality. He was a nice, friendly older man. He often played fatherly types. For example, in 1978’s Superman: The Movie he played kindly Pa Kent.

So for us, seeing his work from the 1950s comes as a bit of a shock. The actor we see in movies like The Big Heat is anything but Pa Kent.

It’s hard to know where to begin with The Big Heat. It is about as dark as movies get, and that sort of makes sense since it’s directed by Fritz Lang, a man Roger Ebert refers to as, “… one of the cinema’s great architects of evil.”

How does Pa Kent wind up in a Fritz Lang movie? If you see the domestic scenes in the movie, and the contrast between them and the rest of the film, you’ll see why. Lang explores evil, both its extremes and its subtleties. Ford plays his part perfectly, enunciating both sides convincingly and leaving us wondering just what kind of man this really is.

I’m not sure the review below is quite how I think about the movie today. I want to watch it again and possibly revise it. I’m wondering now if Glenn Ford’s Det. Sgt. Dave Bannion might not be the original Dirty Harry.

The Big Heat

directed by Fritz Lang

Now this is what a noir film should be. Good guys, bad guys, and a lot of dubious ground between them. (Mind you, it’s not a noir film in the strictest sense.)

Perspective is everything, I suppose, and perhaps that is why (for me) noir works best in black and white. It’s how I came to know them when I was younger. This doesn’t mean more recent, colour noir movies don’t work (just look at Chinatown and L.A. Confidential), but black and white just seems more appropriate.

Maybe it’s the sense of shadow and gray that comes across. It reflects the heart of these stories, an uncertain, dangerous world where it’s hard to tell who is on your side, or even what side you’re on.

As in Gilda, the casting of Glenn Ford is perfect. He plays these parts well. He’s the hero, but not so heroic as to be unbelievable. In fact, the type of hero he plays here is the same type Clint Eastwood got so much mileage out of for so long. He’s the ambiguous good guy.

Then there’s Gloria Grahame who gives a wonderful performance as Debby, the gangster’s girl.

But where The Big Heat really excells is in casting Lee Marvin, an actor who gives Robert Mitchum a run for his money as one of the meanest s.o.b.’s to appear on screen.

Marvin’s explosive and sadistic temper come across as so natural you would be afraid to meet him anywhere but on the screen.

In many ways, The Big Heat is a template for certain types of films (though it certainly wasn’t the first to use this pattern). This is a revenge story. But watching it from this point, over 50 years after it was made, it’s easy to forget that some of the set-ups and patterns were not established in the way they are now so, while in some ways they appear to have a certain stale, over-used quality, the truth is they were fresh and even alarming in 1953.

For example, there is the set-up scene where the domestic life of the Ford character is shattered. The scene becomes the catalyst for the character’s later actions. This pattern has been used over and over again since (again, particularly by Eastwood).

Regardless whether it’s perceived as new or cliche, it works. From start to finish The Big Heat holds you and carries you through its dark unwinding. To be perfectly true to the noir genre, Ford’s character is not as corrupt as he should be (though his revenge could be considered a form of corruption, I suppose). But this is quibbling. It certainly has the noir feel and that is far more important. Noir is really about atmosphere; it’s about tone.

This one is highly recommended.

Movie critics: Like newspapers, a vanishing breed

There’s a troubling post and discussion titled “Death to film critics! Hail to the CelebCult!” over at Roger Ebert’s Journal. It’s about the dying out of newspapers, in this case, newspaper film critics, and the cultural trends we’re seeing now in media of all kinds:

The crowning blow came this week when the once-magisterial Associated Press imposed a 500-word limit on all of its entertainment writers. The 500-word limit applies to reviews, interviews, news stories, trend pieces and “thinkers.”

Even I mused about this, in a not particularly coherent and articulate way, on my other blog with,

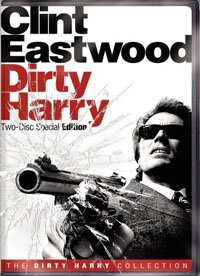

Dirty Harry: should I like it as much as I do?

I’ve always found Dirty Harry a troubling movie. Well, almost all of the earlier, image making movies of Clint Eastwood have been troubling to me, but Dirty Harry tops my list. The reason is simple: from the first time I saw it, I’ve loved the movie but I felt that I shouldn’t.

I’ve always found Dirty Harry a troubling movie. Well, almost all of the earlier, image making movies of Clint Eastwood have been troubling to me, but Dirty Harry tops my list. The reason is simple: from the first time I saw it, I’ve loved the movie but I felt that I shouldn’t.

The conflict is easy to explain. The movie is manipulated to have you cheering for Harry so when, as in a western, the final showdown happens, there’s a cathartic moment, like scoring the winning touchdown on the last play of the game. But then you do a kind of mental double take: this guy with the big gun is actually ignoring the law, being as bad as the bad guys, and feeling justified about it because, well, they’re bad guys and he’s fighting for the good guys.

Harry is essentially a vigilante and in the movie, by creating a perverted, killing bad guy (“Scorpio”), you inevitably root for him because the emotion carries you along and your thinking side is turned off, in a manner of speaking. In his review, Roger Ebert argues that it’s essentially a fascist film, and this may be true, although I think the final scene with Harry tossing his badge in the water could be construed as meaning he’s outside the law now, no different than the criminals he’s been hunting down. It may be the movie wants you to cheer for Harry so it can then say, “Now think seriously about what you’re really cheering for.”

There are lots of people who write about Harry’s appeal to the conservative right, at least of the time (1971), and a frustration with liberal approaches to crime – respecting individual rights, in this case the criminal’s, and abandoning victims. And this may be true, too, though it should be pointed out that operating beyond the law, ignoring victims, is not something to be found on the far right of things. Some, at the far left, have had no qualms about victims when they’ve initiated a violent act for their cause. It’s an attitude that occurs at the far end of things, at extremes, be they left or right.

But what about the movie? Dirty Harry always initiates discussion about the politics of the film and often the movie itself gets overlooked.

First off, I see it as an urban western, and loving westerns that may explain why I like it so much. Harry’s a loner, operating on his own (often to the exasperation of his superiors). He gets little help – some, but not a lot – and he’s after a really bad guy. So it’s framed like a moral tale, the way westerns are … but this leads us into the politics again. It is a moral tale but one a lot more subtle and ambiguous than the usual western because the good guy, well, there’s a reason they call Harry “Dirty.” (This comes up several times in the film, the question of why he’s “Dirty” Harry, with a number of possible reasons thrown out. I think that final scene with the badge is the film’s only suggestion of the real answer.)

First off, I see it as an urban western, and loving westerns that may explain why I like it so much. Harry’s a loner, operating on his own (often to the exasperation of his superiors). He gets little help – some, but not a lot – and he’s after a really bad guy. So it’s framed like a moral tale, the way westerns are … but this leads us into the politics again. It is a moral tale but one a lot more subtle and ambiguous than the usual western because the good guy, well, there’s a reason they call Harry “Dirty.” (This comes up several times in the film, the question of why he’s “Dirty” Harry, with a number of possible reasons thrown out. I think that final scene with the badge is the film’s only suggestion of the real answer.)

Another aspect I like about the movie is how very, very seventies it looks. Of course there are the clothes, the hair, the cars … but I think even more so it’s the overall look of the film. With that look, today it would be called an indie film. Despite some restoration, it still feels gritty and grainy, even when it isn’t. Not only does the movie not look slick, it almost looks anti-slick, as if it’s trying to disassociate itself from Hollywood – a characteristic of a number of movies from that period, like Taxi Driver, for instance.

I was also struck by a nice difference between Dirty Harry and its progeny, more contemporary movies with heroes and really bad villains. Today, a character like Harry would be up against an almost superhuman bad guy. But in this movie, the character of Scorpio, while very bad, is almost something of a screw up. I’m thinking of one scene where he’s out to shoot another victim but gets spotted by the police in their helicopter. Scorpio is bad, he’s dangerous, he’s sick, but he’s not a brilliant criminal mind. He’s not nearly as clever as he would like to imagine himself, and nowhere near as clever as a character such as him would be in a contemporary movie. In other words, there’s a bit more realism to Harry and his bad guy. (And realism is one of the things movies of that period aspired to.)

Finally, I believe one of the reasons this movie is so satisfying is because it understands so well set up and payoff. Like the way good jokes work, with their structure and their rhythm, there are a number of scenes in Dirty Harry that deliver the same way (for example, the “Do you feel lucky, punk?” scenes).

An interesting comparison between Dirty Harry an one of its progeny is the recent revenge film, Man on Fire, with Denzel Washington in the lead role. Whereas in Harry, directing and cinematography are almost self-effacing, with most of the emphasis on story and performance, Man on Fire is very self-consciously directed and very obvious in its cinematography, almost the exact opposite of the Don Seigal film. And whereas Harry is consumed with his hatred for bad guys and indifferent to what he does to nail them (with the possible exception of the end with the badge), Denzel’s character in Man on Fire is almost morose with awareness of being lost to the dark side and, when he goes after the bad guys, is almost like a suicide bomber, willing to do whatever needs to be done and sacrificing himself willingly as a kind of redemption. (And Denzel’s bad guy is much more clever than the Scorpio killer.)

Despite being a film from 1971 and looking very much so, Dirty Harry still works and works brilliantly. It’s just a troubling with its ambiguous politics, and just as thrilling with its cop chasing a killer suspense. I loved it.

(Note: For some of Clint Eastwood’s views on Dirty Harry, have a look at the 1974 Playboy interview, Eastwood Talks Dirty Harry. Amongst other things, when the badge scene from the movie comes up and the reference to a similar scene in High Noon, Eastwood disagees with the comparison saying High Plains Drifter is much more along the lines of the Gary Cooper film.)