I don’t thing many people would argue that Hondo is the best of John Wayne’s movies. Similarly, I don’t many will argue against it being among his best both as a western and as a performance from Wayne. But if ever there was a movie that illustrated what John Wayne did onscreen, how he came across and essentially provided a definition for those words “John Wayne,” it’s Hondo.

The great and debatable Red River

I really go on a ramble here about this movie, though it is more a ramble about John Wayne’s acting and speech pattern than the film. This is considered one of the great westerns by many and I would be among them. However, while I like Wayne in it and think it’s one of his best roles, it is not my favourite John Wayne performance.

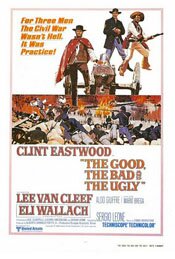

Sergio Leone and a good, odd western

I’m currently reading Marc Eliot’s Clint Eastwood: American Rebel and it inevitably got me thinking about the earlier Eastwood movies, the spaghetti westerns, including The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Below is my lengthy rambling about it from quite a while ago (2000?). For what it is worth …

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

Directed by Sergio Leone

One of the best, and oddest, westerns ever made is The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo). It’s hard to imagine anyone making a movie like this today. It’s too long (it would be argued). Some of the scenes, even shots, are too long. Gee, it takes 30 minutes to introduce the three primary characters. What’s that about?

Continue reading

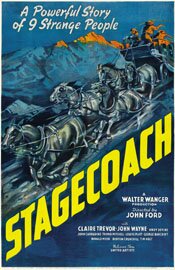

An imposing little Stagecoach from John Ford

When you think of how long it takes to make a movie today, at least a Hollywood movie, it’s quite astonishing to find John Ford cranked out three pretty extraordinary movies in 1939. His “go to” guys in that period were Henry Fonda and John Wayne. (In 1939-1940, he made five films — three with Fonda, two with Wayne.)

The number of movies isn’t the amazing part, though it is notable; what is remarkable is the quality of those films. (The movies are Stagecoach, Young Mr. Lincoln, Drums Along the Mohawk, The Grapes of Wrath and The Long Voyage Home.) For many, that creative glut would be a career. With Ford, some of his best films were still ahead of him.

Stagecoach (1939)

Stagecoach (1939)

Directed by John Ford

For what is essentially a simple western, Stagecoach is a pretty imposing little film. It’s daunting for all the film history associated with it, beginning with the introduction of John Wayne as movie star. (His first starring role was in Raoul Walsh’s 1930 movie The Big Trail. But it was John Ford and Stagecoach that made him a star.)

Interestingly, Wayne wasn’t the big star of Stagecoach. Claire Trevor was. She gets top billing and the movie is an ensemble piece, so no one character really dominates as they do in a “star vehicle.”

The movie also gave us Monument Valley, in Utah, which would afterward be forever associated with John Ford and be the quintessential “old West” landscape with its plateaus, mesas and buttes. And for many, this is the movie where Ford’s cinematic eye for people and landscapes — often low-angled shots; often sky dominated — is first seen.

There is one shot in particular that I loved. The upper two thirds of the frame is cloud fluffed sky. The lower third is plateau with a mesa off to the right; nothing but dessert otherwise, but for a trail with the lonely stagecoach winding along it from right to left, small and vulnerable.

The story is simple enough and one that is standard fare now: a group of people on their way from here to there, in this case on a stagecoach, encountering and overcoming various threats along the way.

In this movie, the threat comes from Geronimo as the stagecoach is passing through hostile Apache territory.

Riding the stage with the marshal (George Bancroft) are the “proper” lady, Lucy (Louise Platt) and the banker (Berton Churchill) … and a number of social outsiders. The hooker, the drunk, the outlaw … all with stronger moral codes than those who make up the proper society from which they’re excluded.

Both Dallas (the hooker) and the constantly inebriated Doc Boone (Thomas Mitchell) have been run out of town by self-appointed guardians of social mores.

Along the way, they meet up with the Ringo Kid (John Wayne), the outlaw. Though a disparate group and one at odds with itself, it is in working together that they make it to their destination.

As far as the story goes, the movie is nothing exceptional, at least not today. It’s significance is in what it means historically, as far as cinema goes, and John Ford’s directorial work.

Even though many of the things Ford did have since been copied and have become fairly common, the look of Stagecoach is still striking; more so when seen in its historical context.

For any serious lover of westerns, this movie is a must.

Apart from being at the start of an extraordinary string of westerns from John Ford that cover decades, it also gives us that moment when the camera moves in on John Wayne’s face announcing, in no uncertain terms, “Meet your favourite star for the next forty years.”

Yes, John Wayne was around for a long time after this movie came out. It should also be mentioned that simply as a movie, this is one very good film.

(In this same year, 1939, Ford would also direct Young Mr. Lincoln and Drums Along the Mohawk.)

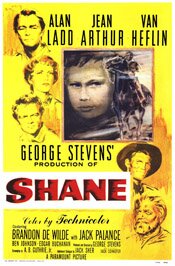

Is Shane too aware of itself as a western?

I wrote the bit below about 8 to 10 years ago after seeing Shane for the first time. It’s strictly a gut response and an attempt to figure out that gut response. But I think it may be time for me to re-watch this movie and see if I still have the same reaction or if I can finally see what many others see in the movie.

Shane (1953)

Shane (1953)

Directed by George Stevens

I’ve never seen Shane before. I haven’t discussed it in a film studies class. I haven’t spent hours in bars or cafes talking about it. I just like westerns, knew it was considered one of the best, and finally decided to watch it. So my reaction to it is, in many ways, fresh and not particularly tainted by what others think of it.

Gut response? I was a bit bored. But I’m not so sure it’s a fault of the movie so much as it’s a problem that the film’s sensibilities are of a time when they were not as frenetic as they are now. People were a bit more open to a more leisurely pace.

On the other hand, some of the problems were not just sensibility and the film’s tempo. Shane suffers, I think, from being a little too self-conscious. It’s a little too aware of the western genre, of its place in it, and of its purpose, which is too comment on the genre and film violence.

Unfortunately for someone from my generation, the story of Shane is one we’re too familiar with from it’s recapitulations, especially the Clint Eastwood films like High Plains Drifter and Pale Rider. Alan Ladd as Shane, despite director George Stevens’ efforts, is a little too clean, a little too smooth shaven. He’s not harsh enough. I’m not sure this is a flaw with the film so much as it’s a flaw with seeing it from a distance in time.

Unfortunately for someone from my generation, the story of Shane is one we’re too familiar with from it’s recapitulations, especially the Clint Eastwood films like High Plains Drifter and Pale Rider. Alan Ladd as Shane, despite director George Stevens’ efforts, is a little too clean, a little too smooth shaven. He’s not harsh enough. I’m not sure this is a flaw with the film so much as it’s a flaw with seeing it from a distance in time.

Shane arrives at a Wyoming homestead as a drifter. He stays for a while with people who are oppressed by cattlemen trying to take over their land. He is distant but suggests strength. Men and women admire and respect him, children hero-worship him. Eventually troubles with the cattlemen come to a head and it is Shane who faces them down.

Of course, there is a helluva lot more to it than that. But that’s the basic premise. It’s the western model Eastwood used many times. The film is self-consciously rooted in a myth and wants to comment on it. It especially wants to comment on violence.

Of course, there is a helluva lot more to it than that. But that’s the basic premise. It’s the western model Eastwood used many times. The film is self-consciously rooted in a myth and wants to comment on it. It especially wants to comment on violence.

The result is a lot of time spent on creating the non-violent world represented by Marion (Jean Arthur) and her husband-farmer played by Van Heflin. (He, by the way, is absolutely perfect in this role; his performance is nothing less than great.)

Unfortunately, the family life, the life of hard work, is not particularly interesting. To appreciate the value of this kind of life you have to live it. To watch it is to go to sleep.

We get to see Shane watching this life, and see his longing for it (an essential element in the film) but again, it’s a bit of a snooze. It’s one of the hardest tasks an artist can set him or herself: to make the lives of nice people interesting for an audience. It is seldom done successfully.

Meanwhile, we are constantly aware that eventually Shane must draw his gun and the big showdown must come. But it takes forever. There are legitimate reasons for why it takes so long, and you can appreciate what George Stevens is trying to do, but … it takes so damn long! And the film is so restrained.

Meanwhile, we are constantly aware that eventually Shane must draw his gun and the big showdown must come. But it takes forever. There are legitimate reasons for why it takes so long, and you can appreciate what George Stevens is trying to do, but … it takes so damn long! And the film is so restrained.

This is all just gut reaction but I really think Shane falls short primarily for one reason: it’s a movie for the intellect and not for the gonads. Westerns are meat-and-potatoes films. They are best when they’re simple. They’re best when they follow formulas. They are best when they tell you things that are true viscerally, not via the brain.

(Note: This review was written back around 2003. It was my initial response to my first viewing of the movie.)

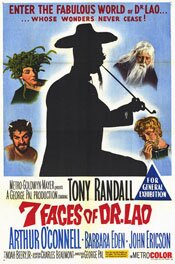

The fantastic western of George Pal

You can see a number of actors best known for their television work in the 1960s and 1970s — Tony Randall, Barbara Eden and Arthur O’Connell — in one of the oddest films: 7 Faces of Dr. Lao.

Is it a fantasy? Without a doubt. Is it a western? I think so. Is it good? Umm … well, that’s one I’ll avoid but I’ll say this — I found it entertaining!

7 Faces of Dr. Lao

7 Faces of Dr. Lao

Directed by George Pal

This movie, 7 Faces of Dr. Lao, is peculiar to say the least, and in its peculiarity is a wonderful fantasy that doesn’t make for the greatest film ever made but a delightful one nonetheless.

Once seen, it’s not surprising to find it is directed by George Pal, who gave us such movies as The Time Machine. Based on a novel by Charles G. Finney titled The Circus of Dr. Lao, the movie is an odd cross between a typical western and fantasies like The Golden Voyage of Sinbad. (That movie was not directed by Pal.)

I make that comparison because you don’t often come across a western that employs old school animation. I believe it was called claymation.

To begin with, though dressed up in western garb the movie takes its first left turn when its lead character, Dr. Lao played by Tony Randall, shows up. He is Chinese – or is he? His accent changes as the situation demands, deliberately. Dr. Lao has brought his circus to the town of Abilone (and Randall plays all the characters in the circus, including Merlin and the Abominable Snowman).

To begin with, though dressed up in western garb the movie takes its first left turn when its lead character, Dr. Lao played by Tony Randall, shows up. He is Chinese – or is he? His accent changes as the situation demands, deliberately. Dr. Lao has brought his circus to the town of Abilone (and Randall plays all the characters in the circus, including Merlin and the Abominable Snowman).

The story is relatively simple and progresses more or less episodically. Dr. Lao comes to a town and using his circus and magic and stories that teach lessons, reveals the town to itself. In doing so, he saves it from disappearing by selling out to a cynical land baron, Clint Stark played by Arthur O’Connell.

The rich and greedy man trying to buy a town to capitalize on a railroad that will soon be coming is a standard, even cliché western story. This movie would be just another, average version of that story except for its fantasy element. (The movie also has its obligatory love story as a romantic John Ericson tries to woo a resistant and bundled-up school teacher, Barbara Eden.)

Several things make the movie stand out. The first is the unusual use of an Asian as the lead character – something unheard of for the period (1964) and especially so for a western. However, typical of the period, the Asian isn’t Asian – it’s a white Hollywood actor (Tony Randall) doing a characterization of an Asian (which, like Mickey Rooney’s Japanese man in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, probably makes the hair stand on end for anyone from an Asian country).

Several things make the movie stand out. The first is the unusual use of an Asian as the lead character – something unheard of for the period (1964) and especially so for a western. However, typical of the period, the Asian isn’t Asian – it’s a white Hollywood actor (Tony Randall) doing a characterization of an Asian (which, like Mickey Rooney’s Japanese man in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, probably makes the hair stand on end for anyone from an Asian country).

On the other hand, as it does this it also suggests that Dr. Lao might not be Asian but rather what is actually the case, a white man mimicking a western world idea of a man from China. So the movie plays it cute and cagey in this repect.

Something else that makes the movie unusual (and mentioned already) is the use of claymation. Who on earth ever heard of that in a western? One result of this is to date the movie. Seen today, the movie either has a nostalgic quality for anyone who grew up seeing these kinds of movies or, for many others, it has a retro, kitsch quality.

For me, the aspect I find truly interesting, and where I think this movie really veers off from its surface western look, is in how the “bad guy,” Stark, isn’t really so bad. His character is as cynical as he is because as a younger man he was so idealistic. In the end, he is happy because he has lost and thus proven wrong. And throughout the movie, he may be the nicest bad guy movies have ever seen. He’s almost always smiling.

For me, the aspect I find truly interesting, and where I think this movie really veers off from its surface western look, is in how the “bad guy,” Stark, isn’t really so bad. His character is as cynical as he is because as a younger man he was so idealistic. In the end, he is happy because he has lost and thus proven wrong. And throughout the movie, he may be the nicest bad guy movies have ever seen. He’s almost always smiling.

7 Faces of Dr. Lao is not a great movie – not by a long shot. But it is very entertaining, moves quickly, and is a more than a little fascinating for its numerous quirks. And as movies go, it’s about retro as retro gets.

True Grit: the last old western?

In some ways, the idea of the Coen brothers redoing True Grit gives me the willies. I would have been 12 or 13 when the Henry Hathaway/John Wayne version came out so it has a kind of nostalgic quality for me. (Believe me, I loved the movie when it came out.)

Unless scheduling changes, the Coen’s True Grit (which stars Jeff Bridges) will be out around Christmas so we’ll know soon enough how the two movies look set against one another. It’s worth noting, however, the movie they are making is not really a remake. It’s hard to imagine the Coens having any interest in that.

From what the publicity and interviews are saying, their movie will be from Mattie’s perspective, the 14 year old girl, and it is an interpretation of the book by Charles Portis, not the 1969 movie.

My guess is that the sunny, bright look of the 1969 version will be toast in the Coen movie. In the meantime, here are some meandering thoughts on the 1969 movie, True Grit.

True Grit

Directed by Henry Hathaway

Distances to cross; troubles to overcome; wrongs to be made right: that’s a western. Good guys, bad guys, horses, boots and guns firing. They all go into the mix because the best westerns are morality tales told within adventures. They are also simple.

True Grit has all these elements and delivers all those things. It also has two old school boys who know their business: actor John Wayne and director Henry Hathaway. Both were nearing the ends of their careers and both had been through a life of working in Hollywood – the old Hollywood. Both were also in a world that was changing, a world enthused about change, and working in a business, cinema, that was enthusiastically embracing change. (Well, the younger parts of it were.)

The movie Hathaway and Wayne made, then, is a kind of reminder that it’s best not to throw the baby out with the bathwater, to use an old expression. True Grit is such an old style western, complete with its swelling strings as riders crest a hill, it could easily become parody.

Yet somehow it doesn’t. I’ve referred to some films as comfort movies and this is one of them. It doesn’t aspire to change the world of cinema. It simply wants to tell a good story.

I think what I like most about this movie is that it is so unapologetic about what it is: an old style western; an old style story. Roger Ebert says this is a movie, not a film. He’s right.

The IMDb synopsis is as simple as the movie: “A drunken, hard-nosed U.S. Marshal and a Texas Ranger help a stubborn young woman track down her father’s murderer in Indian territory.” That’s it; that’s the story this movie tells.

A man is murdered. His 14 year old daughter (Kim Darby) wants him caught and dealt with so she looks to enlist a man with “true grit” to do the job. That man is Rooster Cogburn (John Wayne), a cranky, drinking, one-eyed U.S. marshall. He’s joined by a Texas Ranger (Glen Campbell) who is after the same man but for a bigger reward – the one available in Texas where the scoundrel murdered a senator.

What they don’t anticipate is that the daughter, Mattie, is determined to join them. They aren’t happy with this and try to lose her until it’s more than clear that there is more to Mattie than they expect from a young girl.

What we get on screen through the wonderfully straight-forward directing of Henry Hathaway is story of, yes, grit. It’s about tenacity and resolve and in its way a code of honour. The hunt for the killer, while resembling a revenge movie, is a bit of misdirection. The movie is really about the relationship between Rooster and Mattie.

As far as acting goes, Glen Campbell is in over his head here but holds his own to some degree. But with the great performances by John Wayne and Kim Darby, it doesn’t really matter however.

Wayne received an Oscar for this movie and while you can argue whether it was for his career or his actual performance in True Grit, what he puts on screen in the movie is marvelous to watch. He is so at ease with this character it’s hard to believe acting is work. I think what he gives us, thanks to the character he plays, is a synthesis of a number of characters he’s played in movies like The Searchers, Rio Bravo and even Donovan’s Reef. I suppose you could argue that the Oscar was for his career because, in a sense, the role is his career.

In the end, this is a good movie because it is a good story. It’s also a fascinating movie seen as “the last old western.” Look at how it is shot: bright and beautiful. Notice how workman-like the shots are framed. The camera is only interested in capturing the performance. It wants the performance to tell the story not the elements of film like lighting, angles, camera movement. It’s functional and happy to be so.

I’ll be interested in seeing the Coen brothers’ take on True Grit when it comes out. It should make for an interesting comparison between the film they’ve made and the one Henry Hathaway made. My guess is the two, taken together, will be a revealing study in style and sensibility between eras.

On Amazon:

- True Grit – Amazon U.S.

- True Grit – Amazon Canada

Rethinking Jimmy Stewart – Part 1

I’ve finally finished Marc Eliot’s book, Jimmy Stewart: A Biography. Reading it was an interesting process because, as I did, I re-watched many of the movies Jimmy Stewart appeared in. Between the book and the movies, I’ve re-evaluated my opinion of James Stewart, both the actor and the man.

Truthfully, I didn’t really have an “opinion” of him prior to this as Jimmy Stewart and his movies were always a given for me. By this I mean that when I was young I would watch old movies with my mom and, of course, Jimmy Stewart starred in many of them.

Back then, I wouldn’t have thought about the quality of his performances. They were simply movies – some I liked, some I didn’t.

Not long after that, as I got a little older, I’d “stay up half the night,” as my mother would put it. This meant I stayed up watching The Tonight Show starring Johnny Carson. (I remember when it was just The Tonight Show and I remember when they tagged the “starring …” part to the title.) If memory serves correctly, it ran between 11:30pm and 1:00am (until it was reduced to a 60 minute show).

Jimmy Stewart was often a guest, as he was occasionally on other shows, like The Dean Martin Show (with The Golddiggers!) which my mom and I also watched, usually together.

I think my image of Jimmy Stewart as both a person and as an actor was determined, or defined rather, by the Jimmy Stewart I saw on these shows: avuncular, not too serious, friendly, quaint and drawling. Just a really nice guy in the way a lovable relative might be. There was a disconnect between the George Bailey of It’s a Wonderful Life, the Scottie Ferguson of Vertigo and the Lin McAdam of Winchester ’73.

It’s likely that business of first impressions. Because I came to Jimmy Stewart at the age I was, and he was in the latter portion of his life, he was (for me) defined by that latter half – which was accurate to some degree, but nowhere close to being complete. Once you get an initial idea in your head about someone it’s very difficult to shake loose of it.

But with Eliot’s book and a somewhat different eye as I watched some of Jimmy Stewart’s movies again, I am to some degree free of my initial idea of him and I think the opinion I now have is very much different.

I think now, as I never would have thought before (it wouldn’t have even occurred to me to think in these terms), Jimmy Stewart is easily placed high in the pantheon of Hollywood actors of the period considered The Golden Age.

And I think it’s very possible he should be placed at the very top. When I think of the kind of person he was and the body of work he produced it strikes me as nothing less than remarkable though, in one sense, perhaps inevitable.

Who would have thought that nice, drawling old guy could have produced such work?

Note:

I describe this as “Part 1” because it strikes me there must be a Part 2. What I don’t know is exactly how much I’ll find myself writing. I’ve scribbled enough about many of his movies, so hopefully I can restrain myself and just keep it to one more post … then move on!

Jimmy Stewart rides again

I’ve just started reading Marc Eliot’s book, Jimmy Stewart: A Biography. Having just begun, I can’t say anything about it’s merits, though I can say I read Eliot’s book from a few years ago, Cary Grant: A Biography and enjoyed it. I’m not sure why, but I like reading biographies of Hollywood’s luminaries of the “golden” years. I do have a theory, though.

I think I read these books because they prompt me to go back and rewatch movies, some I had almost completely forgotten about. In Stewart’s case, Wikipedia says he, “… appeared in 92 films, television programs and shorts.” So, although I have quite a few Jimmy Stewart films they are just a smidgeon of what he made. But they’re almost all good ones!

Last night, I decided to go through some of them and decided to start with 1939’s Destry Rides Again. If you haven’t seen Destry, you’ve no idea what you’re missing. It’s a western comedy, with Jimmy Stewart playing a gunshy lawmen brought in to bring order to the lawless town of Bottleneck. It also features Marlene Dietrich. You can take a look at my 2003 review here.

Jimmy Stewart, by the way, was named third Greatest Male Star of All time by the (AFI), just behind Humphrey Bogart and Cary Grant.

And some other Jmmy Stewart movies I’ve written about:

- Anatomy of a Murder (1959)

- It’s a Wonderful Life (1946)

- The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962)

- The Philadelphia Story (1940)

- You Can’t Take It With You (1938)

- Mr Smith Goes to Washington (1939)

Update:

I just found an old post, from 2005, regarding Eliot’s previous book (the one on Cary Grant). The post is titled: Cary Grant — who was that guy?